What do you love in the world and think is worth preserving?

What do you love in the world and think is worth preserving?

Upper Elementary students wrestled with this important question during their class project for the Green and White Bash silent auction. My daughter, Stella, is a student in the Upper Elementary classroom, and I was privileged to assist the children in transforming two blank puzzles into a lively mixed media college. Since the Bash’s theme was “sustaining our future” through the funding of student scholarships and staff professional development, I thought it would be fitting for the class project to address this idea of sustainability. So, I asked each student to design a single puzzle piece that identified their own personal junction of love and preservation. All the pieces joined together to form a single, unified collage.

The project turned out to be both intellectually and artistically challenging for the class. Some of the students needed clarification on the question and took extra care to reflect on the conceptual differences among sustainability, preservation, and conservation. Others thought of multiple ideas and found it hard to choose a single focus for their piece. They would sit in thoughtful silence, rifle through magazines for inspiration, or simply run off to do something else, planning to return later. For other children, the process was easier and they settled into their work instantly. Regardless of how quickly their work progressed, it was humbling to witness the moment when each child’s idea clicked into place. You could sense the wave of clarity and purpose wash over them as they set themselves to task. They would sift through the huge pile of assorted collage papers and magazines and dig through buttons, cork, sequins, pom pom balls, threads, beads, and other odds and ends to find the perfect color, texture, or imagery to convey their idea.

The students’ approaches to composition varied as dramatically as their themes. Some enjoyed working very flat, while others preferred a more 3D composition. Some students chose clipped images and text, while others wanted to incorporate their own drawings. Some designed beautiful miniature scenes of forests and picnics, while others worked more conceptually and built up layers of interest. Each piece was transformed into a unique and carefully crafted work of art.

The students’ approaches to composition varied as dramatically as their themes. Some enjoyed working very flat, while others preferred a more 3D composition. Some students chose clipped images and text, while others wanted to incorporate their own drawings. Some designed beautiful miniature scenes of forests and picnics, while others worked more conceptually and built up layers of interest. Each piece was transformed into a unique and carefully crafted work of art.

After the last student finished, I packed up all of the supplies and took everything home to (literally) put the pieces together. As I assembled the individual pieces into a finished collage, I was amazed by how well the variety of themes and designs worked together. Thirty-seven distinct responses to a single question had morphed into a microcosm of our beautiful, crazy modern world. Elements of nature (birds, oceans, trees) wove through interpretations of social life (family, friends, holidays) and modern living (technology, medicine, Disney). The Upper Elementary class project about sustainability had become an ecosystem of gratitude and hope for the future, where nature merges seamlessly with people, technology, and traditions: very much like a day at Greensboro Montessori School!

About the Author

About the Author

Gina Pruette is a parent and regular substitute teacher at Greensboro Montessori School. In addition to her commitment to the School, Gina is an active volunteer within the greater Piedmont Triad community where she leverages her expertise in marketing and events planning, fundraising, and tech solutions to further the missions of various nonprofit organizations. Gina recently completed Racial Equity Training through the Racial Equity Institute to strengthen work with diverse populations, and she holds a bachelor of arts from the University of Pennsylvania.

Greensboro Montessori School's mission is to nurture children to be creative, eager learners as they discover their full potential and become responsible, global citizens.

Dr. Maria Montessori was a big fan of field trips. In her words, it was important for students to take “outings” or to “go out.” In 1948, Dr. Montessori wrote: “The outing whose aim is neither purely that of personal hygiene nor that of a practical order, but which makes an experience live, will make the child conscious of realities … When the child goes out, it is the world itself that offers itself to him. Let us take the child out to show him real things instead of making objects which represent ideas and closing them up in cupboards.” Hence, the Montessori phrase of “going out” was born.

At Greensboro Montessori School, we take the Montessori tradition of “going out” to heart, as our students take academically aligned, overnight field trips beginning in Lower Elementary. Where lessons in the classroom are a springboard to learning, Montessori outings provide the experiences necessary to move concepts from the abstract to the concrete – to let students apply and expand their knowledge in the world around them.

As our students progress from Toddler to Junior High, they learn the rites of passage, including the field trips, which will greet them along the way. Read about all our adventures, or jump to the grade which interests you most!

Lower Elementary

Second Grade: Students enjoy their first overnight outing in second grade. This year, our second graders will spend a night at The Land, our 37-acre satellite campus in Oak Ridge. This wooded retreat includes a 14-bedroom retreat center, a barn, a covered bridge spanning a freshwater stream, mature hardwoods, peaceful trails, privacy and seclusion, and diverse flora and fauna.

Third Grade: Third graders take annual trips to either Earthshine Discovery Center in the Nantahala National Forest in western North Carolina or the Sound to Sea program along the North Carolina’s Crystal Coast. Students spend two days and three nights building upon their lessons in biology, botany, environmental studies, geography, and physical science.

Upper Elementary

Fourth and Fifth Grade: Fourth and fifth graders rotate between annual field trips to North Carolina’s Outer Banks and Colonial Williamsburg every spring. When at the North Carolina coast, our students experience the region’s rich marine biology and storied history. Students visit national landmarks like Roanoke Island, the first settlement of English colonists, and the Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kitty Hawk. In the words of the National Parks Service, Kitty Hawk is the site where Wilbur and Orville Wright “experimented with flight in the early 1900s, and finally succeed[ed] on a cold winter day with the world's first controlled, sustained, powered, heavier-than-air flight.”

When visiting Williamsburg, students immerse themselves in the history of the American Revolution and explore, as Colonial Williamsburg puts it, “the political, cultural, and educational center of what was then the largest, most populous, and most influential of the American colonies. It was here that the fundamental concepts of our republic — responsible leadership, a sense of public service, self-government, and individual liberty — were nurtured under the leadership of patriots such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, and Peyton Randolph.”

Sixth Grade: Sixth-grade students head to our nation’s capital, where they visit multiple Smithsonian museums, (including the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Air and Space Museum), the National Archives, Arlington National Cemetery, and the National Gallery of Art and Sculpture Garden. Students expand upon their knowledge of national government and civics, while practicing grace and courtesy in a metropolitan city center. Dr. Montessori writes: “A child enclosed within limits however vast remains incapable of realizing his full value and will not succeed in adapting himself to the outer world. For him to progress rapidly, his practical and social lives must be intimately blended with his cultural environment.”

Junior High

Seventh Grade: Greensboro Montessori School’s seventh graders head west to Tuscon, Arizona, where their years of environmental science studies take center stage in this week-long trip. In addition to hiking Kitt Peak, students spend time at the University of Arizona’s Biosphere 2, a state-of-the-art scientific facility. The mission of Biosphere 2 “is to serve as a center for research, outreach, teaching and life-long learning about Earth, its living systems, and its place in the universe; to catalyze interdisciplinary thinking and understanding about Earth and its future; to be an adaptive tool for Earth education and outreach to industry, government, and the public; and to distill issues related to Earth systems planning and management for use by policymakers, students and the public.”

Eighth Grade: Greensboro Montessori School’s eighth graders enjoy an authentic immersion experience in Costa Rica. Our students stay with the Costa Rican families of students from The Summit School, our sister school in Coronado, Costa Rica which is very close to the capital city of San José. Together, our students and the Ticos (a colloquial term for natives of Costa Rica) go everywhere together. They visit volcanoes, complete high ropes courses, and sail through the rainforest canopy on zip lines. They travel to the Caribbean Coast where they walk the beach at night looking for turtle eggs to bury in a nearby protected hatchery. Then, they travel to the Pacific side to snorkel and explore rain forests and animal sanctuaries. They also spend a day in downtown San José learning about Costa Rican history, art, and government. With every visit to Costa Rica, our students return with their eyes a little wider and their lives a little richer as they have their first experience actually living in another culture.

Ninth Grade: An important element of our ninth-grade curriculum is the completion of a year-long capstone project that challenges each student to apply their skills to an area of personal interest that will improve and enhance their world. Similar to a thesis or senior project, the capstone project provides a framework for demonstrating leadership and advanced application of critical thinking skills. To further extend their learning, the students are challenged to design a custom end-of-year outing to include research opportunities for each of their individual capstone projects. In collaboration with a faculty advisor, a past ninth grade class settled on an itinerary traveling throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their route took them to explore tidal pools, tour museums in Seattle, visit a military base in Tacoma, and interview refugees in Vancouver.

The 2018 Green and White Bash is just around the corner, with this year's soirée conveniently falling on St. Patrick's Day! Thanks to generous underwriting from the Proximity Hotel, guests will enjoy an extraordinary, entertainment-filled evening for an all-inclusive ticket price of just $100:

Proximity Hotel and O.Henry Hotel artist in residence, Chip Holton, paints the scene in the middle of an event. Chip will be painting live at the 2018 Green and White Bash? Who will take home his final piece?

- Dine on the culinary creations of Print Works Bistro and Green Valley Grill's Executive Chef, Leigh Hesling.

- Delight with white and red wine; domestic and craft beer; and a custom cocktail inspired by St. Patrick's Day.

- Dance to your favorite hits performed live by Greensboro's own Heartbeat of Soul.

- Watch the NCAA Tournament in our custom-designed sports lounge.

- Take home exciting experiences, gift cards, and hand-made classroom projects from our silent auction.

- Watch Proximity Hotel and O.Henry Hotel artist in residence, Chip Holton, capture the excitement of the evening as he paints live at the Bash (who will win his finished piece in our silent auction?)

We're excited to announce the evening's delectable dinner, sponsored by Olmsted Orthodontics, specializing in Invisalign and Braces. Chef Hesling and his team have worked to serve a delicious and hearty meal to accompany our the evening's festivities.

Designer Cocktail

A Galway Rose featuring Emulsion American Gin from Greensboro Distilling Co.'s Fainting Goat Spirits, St. Germain, rosemary simple syrup, and seltzer

Passed Hors d'oeuvres

Crispy Avocado and Roasted Tomato with lime caviar

Tuna tartar with salmon roe, avocado relish and shaved cucumber

Crispy chicken schnitzel, roasted cremini mushrooms, and vadouvan aioli

Live Action Dinner Stations

Shaved Tête de Moine

Open faced crostini featuring prosciutto fig or mushroom port wine and topped with shaved Tête de Moine cheese from Switzerland

French Dip Sliders

Thinly shaved roast beef, sautéed with onion and mushroom, then topped with brie fondue, and served with aus ju for dipping

Risotto in a Parmesan Wheel

Delight in risotto cooked in a giant Parmesan wheel and prepared to your taste with an assortment of fresh vegetables and seasonings

Seasonal Whole Roasted Vegetables

Roasted cauliflower and carrots with lemon cumin aioli served warm from a traditional carving station

Dessert

A gracious display of fruit-inspired éclairs

Individual dark, white, and milk chocolate mousse with whipped cream

[dt_sc_h3]Sustaining our People[/dt_sc_h3]

We are overwhelmingly appreciative for the inspirational "things" our School received from 70 in 70: The Fund for GMS. This successful fundraising campaign (we raised over $76,000 in 70 days) helped us revitalize our Primary classrooms and fund a substantial slate of classroom grants.

As we enter spring, we look to the inspirational "people" at the core of our School: our students and faculty. The more we can support these individuals, the better prepared they will be to sustain each other and our community. The better prepared they will be to sustain our future and the world. Proceeds from the 2018 Green and White Bash will support our people in the form of financial assistance for students and professional development for faculty.

[dt_sc_button type="type2" link="https://gms.betterworldcollective.com/event/2018-green-white-bash/" size="medium" bgcolor="#62bb46" textcolor="#ffffff" target="_blank" timeline_button="no"]Purchase Tickets for the Green and White Bash[/dt_sc_button]

We recently sat down with Upper School Faculty member, Jonathan McLean, to learn more about Greensboro Montessori School's Junior High Music Ensemble. Here's an edited transcript of our conversation.

Q: What exactly is Music Ensemble?

A: We have a lot of students who want to play a lot of different things or perform a lot of different [types] of music ... anyone from somebody taking violin, to taking piano, to taking singing lessons, to just hanging out at home banging around on the piano. To follow the child - and the best thing for each child - I've found is the Music Ensemble, which is just a big band.

Q: Is Music Ensemble part of students' regular coursework, or is it an elective?

A: The closest thing it's to is an elective. Certain people are required to be in it. If [a student is in] my Creative Labs class and they are always [applying] for positions for composers or being in the band, then yes, it's a requirement they have to be in Music Ensemble. They give up one of their independent studies, which makes it like an elective, and come in [the studio] and rehearse.

Q: How often do you rehearse?

A: One class block every week, which is an hour and fifteen minutes, which is barely enough. But it is Wednesdays. We loose [lots of Fridays and Mondays] every year for [teacher workdays] and national holidays. That's why I put it on Wednesday, so we lose fewer of them. We also have dress rehearsals and sound check rehearsals before any show, [which would] be on a Saturday or Sunday usually, or right after school.

Q: Who can participate in Music Ensemble?

A: Anybody that's already had at least a year’s worth of lessons on a instrument, because Music Ensemble is not for me to teach you how to play an instrument. Creative Labs, actually, is [when] I can spend some time showing a student some stuff about how to play an instrument and then get a student hooked up with an after-school or out-of-school teacher. [Music Ensemble] is an advanced music experience, and the student needs to have already made a commitment to learning an instrument. Vocalists are taking voice lessons, and some have also taken lessons on piano.

Q: Are your vocalists also taking voice lessons?

A: One, two, three. Three of them are. One of them is not. Two of them have taken lessons on piano and have switched to vocals. Once you learn an instrument, particularly piano (because if you go off to music school everybody has to take Piano 101, it's like English Composition 101 to be a writer), you can play pretty much anything.

Q: What is the age range of your current Music Ensemble?

A: 12 through 15, [but we currently have a guest drummer] who is in fifth grade. The [typical] grades are seventh to ninth ... I invited him [to join] for two reasons. One, he's a student of mine, and he's highly advanced for his age. He could play in any band and make money right now if he wanted to. He practices with me once per week and also at home. [Two,] all my drummers graduated. It was an advantageous moment.

Q: What is the single greatest lesson your students take away from working in Music Ensemble?

A: That’s easy. Working in a band is working in a group. When you do group projects in the classroom, how do you assess how much each person is carrying their weight if it's an outside project? We don't know how to do that right now. In class though, it's a little easier ... but in a band, if you are not carrying your weight, everybody knows it. There is no calling somebody out and being unfair and them saying, "No, I know my part." No, you don't, because we have to stop because [someone's] part is wrong, and I don't mean that in a harsh way, it's just one for one, like math. It's either right or wrong. It's either in tune, on rhythm and in the right spot, or it's not. That's the single most important lesson: you cannot hide in a group.

Q: How long have you been teaching Music Ensemble?

A: Music was one of the first things I did when I got to Greensboro Montessori School [in 2002]. The middle schoolers were revolting against the traditional class where students are learning music on recorders playing from the same book I used when I was in Junior High. You have to do something current for adolescents to get engaged. So when you immediately say the word “band,” they want to play.

Q: What have you learned teaching Music Ensemble?

A: The first lesson I learned was the drawback to individual lessons. I think that all people who [teach] individual lessons should have some sort of network where they get their students together to play in an ensemble or a band. I would get a full band together [at Greensboro Montessori School] and each student may have had 2 to 3 years of lessons on their given instrument, and we'd start the song, and we'd play through it, and it would just be cacophonous and terrible. If you just pulled [each musician] out magically and just listened to them, they would nail the song, but they had been taught in a vacuum. As long [as a student thinks they're] playing the song correctly, they're not even tuning in to the other members of the group. So that goes back to the step above learning to work in a group. One, you can tell who is not carrying their weight, but two, its awful, its not pleasant. To teach you to tune into that goes into all the other stuff about brain development and mathematics and what music does to your brain.

Q: What do students new to Music Ensemble need to learn?

A: They need to start listening to each other. It is self awareness and it's being aware of other people, and doing that thing Miles Davis said where everybody pushes and pulls each other. If somebody's lagging behind, it may be because they are having a hard time with a song, so the band has to tune into it, be a team, and slow down a little bit. You can get on them afterwards, like "why were you playing that so slow," but [during] a performance you support your team. But also, it may be, as they get the hang of it, somebody wants to pull the song back, and that sets the mood. Maybe someone wants to push it a little bit, but that's how musicians interact with each other.

Q: What is the most important thing you see your students do in Music Ensemble?

A: All the brain development that goes on after they learn the basics of working in a group, then to listen to each other, and then to get into it [with each other]. What I know as a performer and an entertainer is if you only have one person or 10000 people watching you, if the audience sees that [members of the band are] just up there doing [their] individual jobs, it's going to be apparent to the audience. And even if [the music] is in tune and played well, it doesn’t come together. There is a gestalt that happens when you are into your music, and I think thats the hardest thing to teach the kids to do, because at this age, kids get freaked out when they think people are watching them, and you know what I've learned from sports, it's not their parents watching them. It's their peers. That’s one of their biggest challenges they have - to perform. They don’t want to be awkward, they don’t want to play badly, they don’t want to seem stiff in front of their friends ... which actually, usually causes them to stiffen up.

Q: And where they are as adolescents, that’s an important factor to them, is what their peers think of them?

A: It is at the top of the list according to the best brain research and social and emotional research we have. They literally feel like they're going to die when they're not around their friends. So when their friends are in front of them, they cannot “mess up” in front of them. It's enormous pressure. That's a whole thing that doesn't even affect me. You know, I get nervous before I play, but once I start playing, I settle in. But these guys, that’s a real developmental thing for them to settle into that [and to learn to work through that pressure]. It will hopefully pay off when they get in front of people to present as an individual. Even if [these students] don't go on to be musicians, they will continue to feel comfortable ... presenting themselves, whether its for a college application, a job application, or giving a speech.

Q: As we wrap up our interview, do you have any final thoughts?

A: I am proud of fighting [for music and the arts] as an equal subject to math, science, and language, and I have teammates that have always supported me on that. Now I have a subject called Creative Labs which happens to be music, art, design, and anything like that, but that’s where the 21st century skills are going ... Every day you're getting music and every day you're getting art, which is what the [students] get here. It is equal across the board, but it does take a team that supports that and realizes that. I think that's something vitally different that we do here at Greensboro Montessori School.

Of all the behaviors common to the toddler years, few incite more distress and panic than biting. A single, split-second incident can arouse guilt and embarrassment in the family of the biter; horror in the family of the child who was bitten; and an alarming set of teeth marks on an unsuspecting classmate. Worst of all, the child who does the biting often feels even more bewildered about their behavior than their caretakers do. So why does it happen?

- Exploration. In infancy, your child was programmed to seek information about the world with their mouth, which offered much more tactile and sensory feedback than their not-so-nimble fingers. Now that they are older, they may not have entirely given up their exploratory ways - but now there are teeth to reckon with!

- Frustration. Imagine knowing exactly what you want (a little space, some peace and quiet, that particular red shovel) and being unable to use the words you need to communicate. Toddlerhood can be a frustrating time, and biting offers a quick release of the negative energy a young child cannot verbally express.

- Egocentrism. Young toddlers have not yet developed the recognition that their actions can cause others to experience pain. They only know that biting feels powerful. It solicits an intense response from the child who was bitten ... and, for bonus points, it gets adults pretty worked up too! Which leads us to...

- Attention-seeking. Once a toddler has experienced the dramatic reactions biting brings on, it may become a pattern, wherein the child "tests" us by repeating the behavior over and over to see if they'll get the same result every time.

The Toddler faculty at Greensboro Montessori School takes biting very seriously, and they do their very best to prevent any such incidents while students are at school. However, it's not unusual for a toddler classroom to experience a few biting episodes over the course of the year. Rest assured, our Toddler faculty have a wealth of experience with this behavior, and they can partner with parents to craft a plan to address it. Even better, the plan will conform with the needs and motivations of the child who is biting. If you observe this behavior in your own child, please know that - although alarming - it is a normal and common part of toddler development, and it will pass.

If you'd like to read more about this parenting concern, or if you're experiencing biting at home, we recommend reading Maren Schmidt's blog entitled "Help! My Child Is Biting!"

Valid and reliable scientific research and brain development theory should be the driving force behind any school system.

Sadly, in our country, that is too often not the reality. Too many of our nation’s schools are based on an industrial-era, conveyor-belt, “information-in, information-out” style. Missing in this antiquated approach is the child as an agent and the child as an engaged, responsible, and confident citizen and leader.

We are incredibly fortunate that this is not missing at Greensboro Montessori School. We are fortunate that our pedagogy, our methodology, and our very way of learning, thinking, and being are based in sound scientific theory and research. Dr. Maria Montessori saw to that.

Maria Montessori was a scientist. She was a physician, educator, feminist, barrier-breaker, and innovator who utilized scientific observation and experience working with young children to design learning materials and a classroom environment which foster a child’s natural desire to learn. Dr. Montessori opened her first school (Casa dei Bambini) in 1907, and today there are close to 4,000 certified Montessori schools in the United States and about 7,000 worldwide. She developed a school movement that is perfectly in-line with what modern science and today’s neuroscience research confirm our children need.

Even though the field of modern neuroscience and brain research did not exist during her time, her theories and methodologies have withstood the test of time, and today neuroscience and brain research fully support the Montessori methodology. Our recent professional development visit with Dr. Steven Hughes brought together the worlds of Montessori schooling, brain development, and research. Dr. Hughes is a board-certified pediatric neuropsychologist and past president of The American Academy of Pediatric Neuropsychology. His research interests are on what promotes the growth of executive functions, social-emotional skills, and moral reasoning. Additionally, he and his wife have had a longstanding relationship with Montessori: she is an Association Montessori Internationale (AMI) trainer throughout Europe, and Steve is the founding chair of the Association Montessori International Global Research Committee. Adding Steve’s voice to our ongoing dialogue about how we can provide the best Montessori experience possible was exceptionally valuable to us. Over two full days, we had affirmations of what we do, challenging conversations, new inspirations, and reinvigorated aspirations.

Steve framed many of his remarks around what research has shown students really need for success in life. Yes, good grades on tests are helpful as they create access to future opportunities, but good grades on tests alone are not the most important thing. Research shows they are not correlated with success in life, and they are not what companies like Google, IBM, and Ernst & Young look for in new hires. These companies want individuals who can analytically solve difficult problems, who can work collaboratively within a group, and who can leverage complexity. They want people who can look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it. They want original thinking ... conventional schooling is not aimed at helping students develop original thoughts. Montessori schools, on the other hand, are absolutely set up to elicit and generate original thinking.

What students do need to succeed are the underlying neuro-structures of their brain to be fully developed and finely tuned. Dr. Hughes talked to us about how this all happens in the neocortex, the skin of the brain: the neocortex has the area of a linen napkin unfolded and is just a few millimeters thick. In there are at least 6 layers of interconnecting neurons that are extraordinarily complex. And while you may think our neocortex is for “thinking,” really it’s to build a sensory-motor map of the world and to manage sensory inputs, sequences, and patterns. For example, when we sit on a chair or drive a car, we don’t actively “think” about it, as we have a sensory-motor map of those processes and have built within our neocortex perceived expectations of how something like a chair or car works. When we learn how to respond to existing patterns and how to manage anomalies - that’s how we get good at things. It takes practice. As Jeff Hawkins writes: “Patterns are the fundamental currency of intelligence.”

This model of a cortical homunculus illustrates how our brain perceives our hands as the body's primary receptor of sensory motor input.

The way we build those sensory motor sequences which are stored in the neocortex and are the foundations of all that we do when we’re reflexively thinking (or non-thinking) is by doing things. This is the neuroscientific explanation and defense of experiential education. Dr. Montessori knew this, and it makes sense that she is known by many to be the “mother of experiential education.” As Dr. Hughes puts it, “We are human doings, not human beings.” This picture is of a cortical homunculus in The Natural History Museum of London. In layman's terms, it is a model of how our brain perceives our own bodies -- the hands are the mechanisms for receiving sensory input so they are the single most valuable body part to the neocortex. We survive in the world by manipulating the environments around us - it is our skillful interaction with the world that defines us and allows us to be successful. To find this success, we have to build the neocortex. And to build the neocortex, we have to practice doing things; and we have to develop the mechanics and apparatus so the brain knows how to do new things. Practice is how our brains build themselves. That is what Montessori does. All our lessons in motor skills, self regulation, language, math, and sensorial input are presented in individual, sequential ways which build upon previous knowledge and previous sensory motor patterns. This is how we develop the brain, and how our students find success in both school, and more importantly, throughout their lives.

Dr. Hughes reminded us that Montessori education is based on children having “effortful, motivated, repeated, trial-and-error, experimental interactions with the environment.” That’s what happens in our school every day. It’s what empowers our students to find tremendous success in their school settings at Greensboro Montessori School, in high school, and college. While the focus of Dr. Hughes’ talk was not how the Montessori methodology promotes traditional academic success success, it is part of the story because helping children optimally develop their brains helps succeed in life, which includes school.

Dr. Hughes told us, “when we are talking about a well-constructed constructor, we’re also really talking about IQ.” One pretty good definition of intelligence quotient (IQ) is the ability to construct new sensory-motor couplings. Children who are able to fully develop their neocortex have well-developed sensory-motor maps and are able to best make sense of anomalies and new patterns, and thus solve difficult problems.

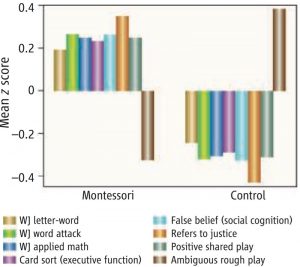

We see these benefits throughout Montessori, and they are documented in Angeline Lillard’s classic Montessori study which was published in 2006 in the journal Science. Through measuring IQ with the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities and studying randomized groups of students in and out of a Montessori program (with an experimental control group), Lillard found Montessori students performed better than non-Montessori peers by nearly a half standard deviation. The best standard deviation improvement from an educational intervention is about a quarter standard deviation; the change of nearly half a standard deviation is monumental.

Lillard's 2006 study found that Montessori students outperformed non-Montessori peers by nearly a half standard deviation in several areas.

It’s also important to remember that scoring well on tests and doing well in school is not necessarily what predicts success in life. We’re not saying school isn’t important, but we are saying success in school shouldn’t be seen as the end result. School success is important because it gives access to future experiences and opportunities. More important is that when your child goes to a school like Greensboro Montessori School, they learn the ability to look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it -- this skill allows them to not only be successful at school, but most significantly, it allows them to be successful in life.

In addition to his fundamental point that experiential education and the Montessori methodology allow students to effectively develop their neocortex and to find success, there were several other key takeaways from our two days with Dr. Hughes. In the various discussions we had, many of the ideas applied to what we can do at home as parents and in the classrooms as educators.

Let the constructor construct.

By taking a neuroscience look at learning, we know that when our youngest children are engaged by doing physical things in their learning, their neocortex in their brains are actively being constructed -- this construction is hard work and requires uninterrupted, child-driven, large blocks of time. Let the constructor construct.

Do not overpraise the child.

Too many parents in our culture praise and overpraise children - sometimes for the simplest of accomplishments. Dr. Hughes reminded us that overpraising children can have negative effects. Research has shown that evaluative feedback (like grades and praise) can stop growth. Dr. Montessori reminds us, “Praise, help, or even a look, may be enough to interrupt him, or destroy the activity. It seems a strange thing to say, but this can happen even if the child merely becomes aware of being watched.” Dr. Steven Hughes jokes with us, “Parents need to really take a good, hard look at your bizzare, irrational, and unnatural desire to praise your children for breathing. Not only does this praise disrupt the child’s concentration, but this evaluative feedback does no good for the developing brain.” While coaching with specific feedback on how to do a task can be valuable, blind praise is not. Again, let the constructor construct.

Never do for the child what they can do for themselves.

Children can often be more capable than we let them be. In Montessori, we are careful to allow the child to do their own work, rather than us do it for them, be it complex math problems or putting on a jacket. We challenge parents to do the same. We do so, because we know from Dr. Hughes that doing and practicing their work allows them to appropriately develop their brains. Yes, it may take more time and patience from us as parents, but let the children do their work -- it’s one of the ways they build their brains.

Montessori does executive functioning very well.

Executive functioning is what we do with our IQ below the level of consciousness – how we organize, make sense of, and make discernments in order to execute and make decisions. From the neuroscience perspective, this is called cognitive flexibility and is an important part of executive functioning: when Plan A doesn’t happen, we have to have the flexibility and adaptability to create Plan B. Executive functioning is developed when the neocortex is allowed to develop those sensorial-motor maps through repeated practice and doing.

Concentration is fundamental to Montessori.

Classrooms at Greensboro Montessori School are based on giving children time to concentrate. Too many other school systems shuffle children from one idea or class to another every 34 minutes. From the neuroscience perspective, Dr. Hughes told us that concentrating is engaging the frontoparietal network in effortful cognitive tasks, where rules or information learn to be utilized and to guide behavior. Dr. Montessori knew that “Concentration is the key that opens up the child to the latent treasures within him.” Once again, her methods developed over one hundred years ago are today confirmed by modern neuroscience research. This concentration is how we develop capacity and capabilities to link together all our future skills and ultimately succeed in a complex world. It’s the foundation for us to learn how to look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it.

Never interrupt the concentrated child.

Children innately want to explore, to touch, and to engage in certain types of work or projects. At various parts of their developmental journey, they are drawn to different things. And it is nature’s design that they want to do some work, or age-appropriate activities, again and again. Somehow, they know they need to practice them. And through modern neuroscience, we now know very well that this practice of building sensory-motor maps in the brain is one of the ways the neocortex develops within the brain. We know this is the foundational building block for future thinking. And through research and brain scans, we know that when the child is actively working and concentrating, they are literally building their brains.

When this is happening, this brain building, there is nothing we can or should do. We need to step back, let the child direct, and let the child be inspired. Never interrupt the concentrated child; it is then when they are constructing. In a Montessori classroom, we build time and systems to allow children to find real concentration and to focus on big work. While they aren’t able to work on one project or subject the entire day as there are other lessons and other parameters for the day, we do pride ourselves in having blocked times (sometimes as long as three hours), where the children can focus on their work and consequently develop their brains. As parents, we should work to not interrupt a focused and concentrated child; while a quick picture, a redirection, or new idea from us may be so tempting… try to resist that urge, knowing that concentrated work is very important, that our children are literally developing their brains.

For two full days, Dr. Steven Hughes toured out school, and engaged with our faculty, our students, our parents, and our administration. When he stepped away he wrote to us: “I can tell you are heading into one of those wonderful chapters in an organization with the right people are on the bus, and the bus is headed in the right direction. One can’t always force those conditions but when they are present amazing things can happen. I’ll look forward to hearing about the amazing things happening at Greensboro Montessori School in the future!’