Greensboro Montessori School hosted two teacher workdays this fall, each dedicated on professional development. Classrooms were closed giving our team uninterrupted time to focus on learning new skills and growing as educational professionals. So how did the team use their time?

During our September 20 workday, faculty paused to reflect on the work we do with students every day and our approach to guiding them in their meaningful work. Nancy VanWinkle, instructional coach, and Jessica White Winger, director of student support, led a workshop designed to build teachers’ tool sets for preparing the environment, particularly expanding the resources of the prepared teacher. The theme was building a “Community of Reflective Practitioners,” with a focus on leveraging the collective experience of the educators in the room.

Teachers worked in mixed-division groups, with varying years of experience in the field. The morning opened with a grounding activity in which teachers were shown photographs of individuals who have affected positive change in the world. These individuals have raised awareness around difficult issues, often putting their lives and work at risk to do the “right” thing. Teachers were asked to work with their groups to list the qualities of one of those changemakers. Following a share-out, the group reflected on how we can encourage these qualities in all of our students. This impactful exercise grounded us in the knowledge that each child is under “self construction” and we have the big responsibility of allowing their true light to shine, while helping guide them in becoming their best self.

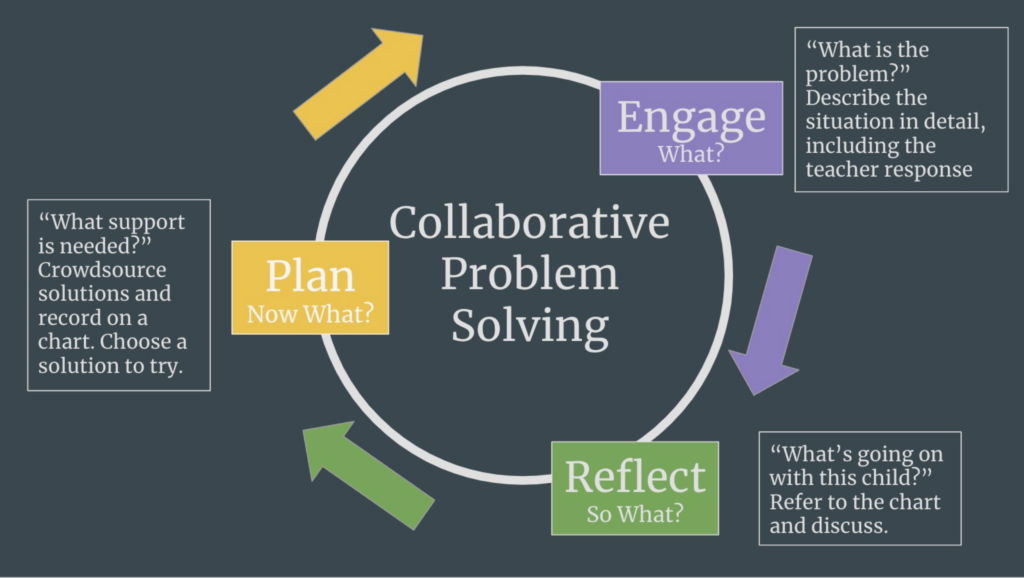

Following this exercise, Nancy and Jessica shared what resources and experiences they have to support teachers during the 2023-24 school year. As our instructional coach, a role dedicated to support faculty in their professional development, Nancy worked closely with Jessica to design a collaborative problem-solving approach for schoolwide implementation. The model offers teachers a practical tool for seeking input from one another and leveraging the cumulative knowledge of our faculty and staff.

This collaborative problem-solving model has teachers sharing a specific behavior they are experiencing with a child in their classroom. A group of educators, with one facilitator and one recorder, reflects on the overall question, “What’s going on with this child?” and what are the unmet needs, lagging skills, or obstacles that the student might be encountering? By looking at the heart of the issue, we honor the child and seek to better understand what their behavior is telling us. The facilitator then takes the group through a series of brainstorming questions, while the recorder writes strategies and suggestions. In the end, the teacher chooses a strategy to try out for a week and agrees to report back to the group. At that point, they may revisit the brainstorm and select another strategy to try.

After modeling this process for everyone, teachers split into their mixed-division groups to practice the model. The value of this collaborative approach is vast, as it’s an opportunity for teachers to gain new perspectives and insight, helping create a shift in paradigm and introducing new ways of responding to student needs. It’s about connecting with colleagues and taking a child-centered approach, as much as it’s about reflecting on our own vulnerabilities and finding strength in the process. It is not about “fixing” a behavior, but opening ourselves to trying new approaches and embracing the spirit of the child.

During our October 6 teacher workday, our group of reflective practitioners reunited to share how our new system of collaborative problem solving is helping them in the classroom. Mixed-division groups reported out on strategy successes and areas of growth. More teachers had the opportunity to share a new challenge with their groups and seek strategies to try. Faculty feedback for this process has been overwhelmingly positive, and we are excited to be working closely together to authentically support students and to address their most critical needs.

Teachers spent the latter half of the workday looking at the scope and sequence of their Montessori curriculum, evaluating it with a fine-toothed comb to ensure fidelity and best-practice in every classroom. This “big work” is just one more way we are reflecting on our practice and ensuring that every student at GMS is engaged in meaningful work as they progress from Toddler through Junior High.

Through intentional planning, we make professional development at GMS relevant and meaningful. We consistently follow-up with faculty to ensure we are meeting their needs and supporting their professional growth. From workshops, trainings, and conferences to observations at other schools, professional development offers inspiration and connection for GMS teachers.

Dr. Maria Montessori was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949, 1950, and again in 1951. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, becoming the youngest man to receive the honor at the time. They were both influenced in their work for peace by Mahatma Gandhi. In the 1930’s Maria Montessori met Mahatma Gandhi while she was living in India, and Gandhi gave a speech to Montessori teachers in training in London in 1931. There he said of her work, “You have very truly remarked that if we are to reach real peace in this world and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with children.” While Dr. King did not meet Gandhi in person, he referred to him as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.”

These three peacemakers have been great influencers across cultures. Dr. Montessori established educational training programs that have led to thousands of schools all around the world. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. organized peaceful protests that changed civil rights laws in the United States and inspired future peaceful protest around the world. They all changed the world through peaceful efforts.

At Greensboro Montessori School, we implement the peace curriculum at every age level - from guiding toddlers to self calm to teaching peaceful conflict resolution in our preschool and elementary classrooms, to visiting the United Nations in Junior High. We seek to provide experiences for children to understand and access the peace within themselves, to relate with other people, cultures, and the environment, and to embrace the complexity of humankind. When children are given opportunities to practice peace within themselves, they will be able to share it with others and seek it out in the world.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically.” These peacemakers have influenced generations. And inspired by their work, Greensboro Montessori School is educating the next generation of peacemakers and innovators.

Greensboro Montessori School partners with the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) to use Measure of Academic Progress (MAP) Growth assessments. MAP Growth is a computer-adaptive test for measuring individual student achievement and growth in math, reading, and language usage.

We've chosen MAP Growth because it is a student-centric approach to standardized testing. Unlike paper and pencil tests, where all students are asked the same questions and spend a fixed amount of time taking the test, MAP Growth is an adaptive test. That means every student gets a unique set of test questions based on responses to previous questions. At the end of each test, teachers are able to determine what individual students know and are ready to learn next.

Unlike traditional standardized tests, MAP Growth testing is administered twice a year, enabling us to measure our students' individual growth over time. Teachers may also use test results to further inform instruction, personalize learning, and monitor student growth.

While we are not a test-driven school, we know test taking is a practical life skill students need in preparation for high school and college. MAP Growth tests are one form of assessment we use, in conjunction with other methodologies of formative and summative assessment given throughout the school year.

About MAP Growth

No. As a computer-adaptive assessment, MAP Growth will provide questions to test the upper limits of your child's skills. Every student will miss questions. The MAP Growth guides suggest that students should expect to miss 40-60% of their questions.

There is no particular score for which students should aim. Instead, your child's individual MAP Growth Report will contain a RIT score. This score represents their achievement level at the time they took the test. As a partner in your child's education, we are less concerned one-time scores and will focus more attention on students' growth measures between assessments.

During MAP Growth

After MAP Growth

Preparing for MAP Growth Assessments

There is nothing families need "to do" in preparation for a MAP Growth test. We encourage families to follow the child – provide the level of support they need to feel successful. This could vary between treating an assessment day like any normal school day to practicing questions on a sample to get comfortable with the format, to talking with your child about the practical life skill of testing (i.e., tests are part of education and you should do your best, and you should not worry or stress over tests).

If you'd like to provide a strong framework for your child before and during a test, we have these tips:

The Night Before

- Relax and have fun.

- Enjoy a healthy snack an hour before bedtime.

- Get a good night's sleep.

The Morning of the Test

- Fill up on healthy, complex carbs and protein.

- Slow-release carbohydrates, like whole rolled porridge oats, whole grain bread, low-sugar muesli, and fresh fruit with a low glycemic index, help provide consistent energy levels throughout the morning.

- Proteins, such as milk, yogurt, or eggs, keep students feeling full and can lead to greater mental alertness.

- Prepare and bring a healthy midmorning snack to school.

- Arrive at school on time – no later than 8:15 a.m.

- Connect with a friend or teacher if you have pretest jitters.

During the Test

- Take three deep breaths.

- If you don't know the answer, give your best guess and move on.

As they do every spring, Greensboro Montessori School's Junior High students recently engaged in their final Great Debate of the year in history. Students addressed and argued both sides of two debates. The first questioned whether the purposes of government are best served by an authoritarian approach. The second questioned whether the primary role of a government should be to meet the needs of its people. The debates provide Junior High students the opportunity to argue in a logical and clearly defined manner.

While The Great Debates are usually hosted in the classroom, this year's final debates were argued virtually through Google Hangouts. 57 participants, including students from both Junior High and Upper Elementary, attended the event, deepening their understanding of many forms of government and economic systems, including authoritarian, capitalist, communist, and socialist.

While The Great Debates are usually hosted in the classroom, this year's final debates were argued virtually through Google Hangouts. 57 participants, including students from both Junior High and Upper Elementary, attended the event, deepening their understanding of many forms of government and economic systems, including authoritarian, capitalist, communist, and socialist.

How the Debates Work

Teams of two or three students are given their topic in advance, but they do not learn which side they are on, for or against, until the morning of the debate. As a result, they must analyze and evaluate both sides and research and compile points and examples supporting both arguments. Each student writes two formal position papers, one for each side of the argument. This helps them broaden their thinking and mental flexibility.

The debates follow a modified version of standard debate procedure, with an opening argument, sometimes shared by two teammates; time for preparation of rebuttal; and then closing arguments and rebuttal, by the remaining member of the team. Faculty members observe, discuss and provide extensive oral feedback to the teams about the debate.

The debates follow a modified version of standard debate procedure, with an opening argument, sometimes shared by two teammates; time for preparation of rebuttal; and then closing arguments and rebuttal, by the remaining member of the team. Faculty members observe, discuss and provide extensive oral feedback to the teams about the debate.

How Topics are Selected

The topics of the debates are drawn from subject matter the students have discussed in history classes during the preceding several weeks. Students are encouraged to go beyond the class discussions in gathering information and building their arguments.

The process allows students to go beyond what they have learned and apply it to larger questions, to develop their reasoning and ability to build and support logical arguments, and to gain confidence and develop greater precision in presenting their thoughts persuasively.

How We Learn

As Junior High students move into and through adolescence, it’s imperative they receive authentic support for their burgeoning philosophical questioning, curiosity in the world around them, and deep desire for belonging within their peer group. Greensboro Montessori School honors these needs through the concept of valorization, which is a pillar of our Junior High curriculum.

Valorization is the process of understanding you are a strong and worthy person. It is the process of self-actualization and fulfillment. It is not about surviving hours of arbitrary homework or memorizing facts for the next test. It’s about completing meaningful work, unleashing academic excellence, and solving real-world problems.

The Great Debates are just one example of how Greensboro Montessori School students experience valorization by developing self-worth, skills, and courage through purpose-filled work. Learn more about how we build valorization through our science curriculum in our recent blog about Trout in the (Indoor, Outdoor, and Virtual) Classroom.

If you are interested in learning more about Greensboro Montessori School's student-centered Upper School serving motivated learners in fourth to ninth grades, we encourage you to schedule a virtual information session. We welcome an opportunity to meet you, learn more about your family, and explore Greensboro Montessori School could partner with your family.

After a long day away from our children, we parents are eager to hear all the details about how they have spent their time. However, so often our queries of “What did you do today?” are met with the same predictable response: “Nothing.” For children, distilling the many details and experiences of a full day at school into an anecdote or two is a tall order. What tools can we use to get them talking about their learning?

Vidigami

Through the Vidigami private photo sharing platform, you get to see moments of your child’s day at school. Viewing photos of your child engaged with Montessori materials can inspire great conversations. Children, especially those younger than five, are not yet able to summarize and describe the many things they experience over the course of a full and stimulating school day. However, photos offer visual cues that trigger a child’s memories and invite them to comment on specific materials and activities. There are many different ways to talk about these photos with your child, and we've provided some suggestions, which focus on your child's intrinsic motivation. Enjoy these special conversations as you allow them to teach you what they are learning at school.

- Ask your child to tell you about the photo. You may learn what they see in the classroom, or what they remember about the moment, and it may be much more than meets the eye.

- Say what you see without judgement. “I notice you are in the classroom.” “Do you know the name of that work?” “There are a lot of colors in your drawing.”

- Speak about their efforts instead of praising their product. “You really look like you are concentrating.” “Is that the first time you have done that work?” “I see your smile. What did you like about that work?” “Are you building with those blocks?”

Intrinsic Motivation

Listening to your child talk about the photos and speaking without judgement encourages your child's intrinsic motivation – it allows them to continue to work for their own sake, rather than for any praise from adults. As Montessori teachers, we get to witness this intrinsic motivation every day. It looks different at each age grouping and is a critical element to Montessori education. Many elements of the method foster intrinsic motivation without reward and judgement, such as control of error in the materials, allowing for repetition, assessment through observation, and relying on peers as sources of feedback and inspiration. Teachers try never to interrupt a concentrating child or judge their work. Instead, they seek opportunities for meaningful conversations before or after a student's work cycle.

As Montessori observed children, she saw time and time again the intrinsic motivation in the child to work through repetition for long, uninterrupted periods of time. In a book that examines Montessori’s relevance to today’s educational practices, "The Science Behind the Genius," Angeline Lillard refers to several current research studies confirming that rewards and punishments not only negatively impact intrinsic motivation, but also how a student performs on the task. Traditional reward methods used in most schools may actually hinder a child’s performance. Given the opportunity, children are capable of learning to take personal responsibility for their actions.

“Like others I had believed that it was necessary to encourage a child by means of some exterior reward that would flatter his baser sentiments … in order to foster in him a spirit of work and of peace. And I was astonished when I learned that a child who is permitted to educate himself really gives up these lower instincts.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

As a Montessori school, we believe deeply in educating the whole child: their academic, psychological, critical-thinking, moral, and social-emotional selves. In addition to the academic lessons and works your children are engaged in daily, our teachers and staff are also guiding your child through other very important lessons to help them with their moral and social-emotional development. For example, teachers give explicit lessons related to grace and courtesy, facilitate discussions at the peace table, and encourage collaborative work and play daily.

And, it turns out, research from our School confirms that we are doing this pretty well …

The Gratitude Project

We recently worked with Professor Jonathan Tudge and his team from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro ("UNCG") to study the development of gratitude as a virtue. As a virtue, gratitude goes beyond a positive feeling when something good happens. Virtuous gratitude is a disposition to act gratefully when someone else does something nice for you. Dr. Tudge explained it to me this way: “Saying 'thank you' is polite, but hardly a virtue. What makes gratitude a virtue is when beneficiaries of good deeds or significant help want to do something back for their benefactor if they have the chance to do so. That first act of generosity, followed by grateful reciprocity, leads to building or strengthening connections among people.”

In previous cross-cultural research, Dr. Tudge and his team found that most children develop this type of gratitude between the ages of 9 and 13, although the age differed depending on the cultural context. In their study, children in the United States developed virtuous gratitude at later ages than other cultures. Keeping this in mind, Dr. Tudge decided to target a new intervention designed to encourage the development of gratitude within adolescents.

Dr. Tudge and his team came to our School to explore this intervention. After working with our Upper School students, they stumbled upon a ‘good’ problem with their research: far more Greensboro Montessori School students exhibited virtuous gratitude than they expected. Our Upper Elementary and Junior High students expressed gratitude at much higher rates (67%) than did children in non-Montessori settings in the United States (46%). In addition, our students were almost twice as likely to express autonomous moral obligation (79%) than were children in non-Montessori schools (44%). Defined originally by Jean Piaget, autonomous moral obligation is a decision-making framework whereby moral decisions are made based on intrinsic motivations to do the right thing.

Dr. Tudge and his team were puzzled by these anomalous findings. Why did our students score higher than other American children, even when compared to other well-regarded private schools in the Greensboro area? And how are these findings related to Montessori pedagogy and culture?

Gratitude in the Montessori Classroom

In our discussions with Dr. Tudge, we discussed the way Montessori teachers prepare the environment to communicate honor, respect, and gratitude to the child. We also described the ways in which our teachers model gratitude and respect when they speak and interact with their students. In time, this becomes our students' definition of "how it's supposed to be.” In addition, we delineated how our grace and courtesy curriculum creates both a framework for community interactions and a schoolwide culture of character.

In collaboration with Dr. Tudge and his team, I presented the results from our Upper School students’ involvement with Dr. Tudge's gratitude study at the Association for Moral Education’s annual conference in Seattle, Washington.

In the presentation, we hypothesized that our students' high rates of gratitude could be due to several specific tenets of Montessori philosophy:

- Specific lessons about grace and courtesy provide explicit guidance on character development from a young age.

- Daily practice of grace and courtesy increase opportunities for proximal processes related to virtue development.

- Mixed age groupings of children may expose younger children to older children are further along in virtue development.

- Peer interactions encouraged from toddlerhood may increase opportunities for the development of mutual respect.

Dr. Tudge and his team also did some work with our Lower Elementary students. Tudge’s team again noted that so many of even these younger children (aged 6 to 9) expressed virtuous gratitude. Dr. Tudge reflected: “We think that this must say something about the character-based focus of the general Montessori curriculum, because a far greater proportion of Greensboro Montessori School children expressed gratitude than elsewhere.”

Dr. Jonathan Tudge and his team from UNCG discuss gratitude with Lower Elementary students from Greensboro Montessori School Students.

Character Education at Greensboro Montessori School

Overall, the results suggest that a Montessori environment is conducive to developing virtuous gratitude and autonomous moral obligation. These results – while surprising and interesting to the UNCG team and other researchers and educators at the Association for Moral Education conference – are not really that surprising to us. Focusing on strong character education is a key tenet of Greensboro Montessori School. A deep respect towards classmates and other people is so integral to our culture that it's not that surprising our Elementary and Junior High students authentically take their sense of gratitude to a level beyond just saying “thank you.”

If you were lucky enough to be at Greensboro Montessori School last Thursday night, or with us via the livestream, you were treated to quite a show! Simply put: our fourth, fifth, and sixth graders' 17th annual Fare Faire production, “Back to Families Feudal,” was fantastic: high-quality, well-researched, technically sound, aesthetically powerful, and laugh-out-loud funny.

Fare Faire is a rite of passage for Upper Elementary students at Greensboro Montessori School. This annual theatrical production integrates students’ language arts, history, and performing arts curriculum. As students learn about the medieval historical period, they also read related literature and work together to bring a story to life on stage. The name, “Fare Faire,” is a creative play on words which highlights the communal meal Upper Elementary students and their families enjoy before the student-led performance - this year the potluck dinner of years' past gave way for a sweeter dessert feast.

And with all this work, all this project-based learning, all this technical and logistical demand of putting on a 31-person theatrical production, I have to ask: where were the teachers? I barely saw them all night.

I heard Cathy Moses and Tessa Kirkpatrick may have been backstage to reassure a few worried students or help with a tricky transition; and I saw Jonathan McLean and John Archambault lingering over at the light and sound board, and even once saw them each use the spotlight, but I think it was only because the sixth grader running the sound board told them what to do. The rest of the time, I saw the teachers pretty much relaxing and enjoying the show, sometimes just leaning against the bleachers or even sitting in the audience. When I complimented them on the show, they said, “Yes, the students did a great job.” While I cannot underscore the intense, long, and passionate hard work the faculty have put in over the past three weeks, one thing was crystal clear Thursday night: the teachers were not in charge of this show. The students were.

I heard Cathy Moses and Tessa Kirkpatrick may have been backstage to reassure a few worried students or help with a tricky transition; and I saw Jonathan McLean and John Archambault lingering over at the light and sound board, and even once saw them each use the spotlight, but I think it was only because the sixth grader running the sound board told them what to do. The rest of the time, I saw the teachers pretty much relaxing and enjoying the show, sometimes just leaning against the bleachers or even sitting in the audience. When I complimented them on the show, they said, “Yes, the students did a great job.” While I cannot underscore the intense, long, and passionate hard work the faculty have put in over the past three weeks, one thing was crystal clear Thursday night: the teachers were not in charge of this show. The students were.

In my 20 years of independent school education, I’ve seen plenty of wonderful “student-led” productions. But not until our very own Fare Faire, have I seen a show so incredibly run by the students. When we walked into the Gym, it was a student decorations manager who had transformed the space into a medieval stage; where there was a line forgotten, it was a student director who whispered a line; when there was a costume glitch, it was the student costume manager who responded; whenever someone missed a cue to come on stage, there was a student stage manager giving them a gentle shove onto the stage; or when one of the mics crackled, it was the student sound manager who adjusted the board settings.

Sixth graders have the opportunity to step into leadership roles for the production. Stella and Mahinda were the directors. Leila the stage and decorations manager. Whitley was in charge of costumes, while she and Stella also worked with Jillian Crone to spearhead marketing for the show. Andrew was in charge of sound and lights, while Mohamed was in charge of microphones. Dalia was in charge of props, and Kylee in charge of photography. Leading their fourth and fifth grade peers in producing Fare Faire is a capstone experience for these students. They had been preparing for that responsibility and honor all throughout the first two years of their three-year cycle.

Our three-year Upper Elementary program has always delivered a strong and unique learning experience for our students. Building on the Montessori skills and foundations that have been developed throughout the Primary and Lower Elementary divisions, our fourth through sixth graders are empowered to come into their own as they transition to the Upper School. They take responsibility for their learning in real-life applications; they develop all the academic and social-emotional skills they need to thrive in life; and they learn who they are and how they will step into the world. It is a critical time in the students’ development. And it is big work.

And that big work is guided by a group of inspired and hard-working “teacher-guide-people,” as the faculty sometimes call themselves. Each subject matter experts themselves, they know that so much of the Montessori approach is correctly and carefully setting up the prepared learning environment to guide the students to their own success. With most traditional schools, and even some great schools that try to be more innovative, the model is teachers as the "sage on the stage," filling students with facts and information; not at our school. It is teachers as guides, teachers as inspirers, teachers as coaches, and teachers as expert listeners, researchers, and observers to see what each and every student uniquely needs.

So, where are the teachers?

They are there, every single step of the way, knowing how to both nurture and challenge, knowing how to inspire and empower students to do the work themselves, and knowing when to step back and let the students take ownership and responsibility for their own work, for their own success, and for their own theatrical production, as was the case during the simply fantastic Fare Faire production on a recent and chilly Thursday night in January.

Sara Stratton leads Primary students in making dressing for their strawberry spinach salads.

Springtime is always joyful in Greensboro Montessori School's organic gardens. Winter buds swell and burst, capturing the eyes and hearts of community members, no matter their age! Flowers of all kinds call to us and to our pollinator friends, and sooner than we realize, we reach the height of the season.

This year brought a colder and wetter forecast than in the past. We’ve still yet to harvest our first sugar snap peas, but the strawberries and spinach are out with a vengeance! We continue to enjoy the lushness all the early rain and cool weather brought, even as temperatures rise. Here’s a brief update from our spring adventures!

Primary and Lower Elementary have enjoyed plenty of weeding, watering, planting, and tasting. We just finished a week full of strawberry spinach salads, with a bit of fennel and spring onions thrown in for fun! (Check out the recipe below if you’re interested in trying this at home.) In Upper Elementary, we celebrated the conclusion of our Student Climate Change Summit art exhibition with a persimmon-ginger-honey ice-cream party! Everyone agreed it was fun to make and even better to taste!

Thanks to everyone who attended our Spring Community Garden Workday in the Primary Garden. Together, with roughly 20 volunteers from our school community (ranging in age from 18 months to 70 years old!), we had a blast and accomplished a swath of projects:

- A group of students and dads built a blackberry trellis.

- Sara Stratton supervised several painting projects: our new fence, sink, and picnic tables got all glammed up in a matter of minutes!

- Another dad mixed concrete, which every child who came to the workday used to make a decorative stepping stone.

- Nearly everyone weeded, watered, snacked, swept, and generally left the space looking wonderful for the students, faculty, administration, and all the special guests we welcome in the spring!

What else have we been up to in the organic gardens this spring? We have been incredibly blessed with the generosity of The Fund for GMS. You may have noticed several new Adirondack chairs, benches, swinging benches, outdoor sinks, and chalkboards in all three of our organic gardens. We also have a new Lower Elementary toolshed coming soon. The students have relished in these new additions to their outdoor classrooms, and we couldn’t be more grateful to have such gifts shared with us from within our school community. Thank you, for your continued support of environmental education at Greensboro Montessori School. From all of us on your environmental education teaching team, Happy Spring!

Strawberry Spinach Salad

For the salad:

- 1 pound fresh spinach, washed and spun

- 1 pound fresh strawberries, washed and dried

- 2-3 spring onions, optional

- 2-3 leaves fennel, minced

For the dressing:

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1/8 cup balsamic vinegar

- 1 tablespoon honey

- 1 pinch cinnamon

About the Author

About the Author

Eliza Hudson is Greensboro Montessori School's lead environmental educator. Eliza holds her bachelor's degree in biology from Earlham College in Richmond, Ind. She has built and tended school gardens, taught hands-on cooking lessons and connected local farms to school programs working for FoodCorps. Prior to joining Greensboro Montessori School in 2014, Eliza was a classroom and after-school assistant at the Richmond Friends School, a farm intern at a family-owned farm in Ohio, and served as assistant director at a summer day camp in an urban community garden in Durham.

Greensboro Montessori School has taught environmental education since 1995 and has been permaculture gardening on its campus since 1997.

Greensboro Montessori School's Junior High student council members usually plan three dance parties a year, one each in the fall, winter, and spring. Whether an upcoming dance is your child's first or they have attended these kinds of functions before, we have some details to help you plan ahead.

When: Greensboro Montessori School dances are on a Friday night from 7 to 9:30 p.m.

Where: Dances are hosted in Greensboro Montessori School's Gymnasium

Who: Attendance is limited to currently enrolled students in grades six through nine. In general, students may not bring guests from other schools. In some instances, Greensboro Montessori School has invited other independent schools in the Independent School League to attend dances, but this is the exception to the rule.

Attire: Students may choose to dress up or wear regular clothing. Attire must follow Greensboro Montessori School's dress code. We ask all attendees to wear soft-soled shoes that will not scuff or leave marks on the gym floor.

Chaperones: All dances are chaperoned by faculty and staff from Greensboro Montessori School. On the night of the dance, parents may drop-off their child at the Gymnasium entrance at 7 p.m. and return at 9:30 p.m. when the dance is over. The School always provides the name and cell phone number of at least one chaperone in a personal email to parents.

Cell phones: Students are permitted to bring cell phones to dances.

Entrance Fee: Students pay $5 cash at the door to attend dances.

Music: All Greensboro Montessori School dances have a DJ who is a current student. They develop a playlist based on student requests and submit this playlist for review by their faculty advisor. The faculty advisor reviews the list for content and language and approves only those songs which are age appropriate.

What do you love in the world and think is worth preserving?

What do you love in the world and think is worth preserving?

Upper Elementary students wrestled with this important question during their class project for the Green and White Bash silent auction. My daughter, Stella, is a student in the Upper Elementary classroom, and I was privileged to assist the children in transforming two blank puzzles into a lively mixed media college. Since the Bash’s theme was “sustaining our future” through the funding of student scholarships and staff professional development, I thought it would be fitting for the class project to address this idea of sustainability. So, I asked each student to design a single puzzle piece that identified their own personal junction of love and preservation. All the pieces joined together to form a single, unified collage.

The project turned out to be both intellectually and artistically challenging for the class. Some of the students needed clarification on the question and took extra care to reflect on the conceptual differences among sustainability, preservation, and conservation. Others thought of multiple ideas and found it hard to choose a single focus for their piece. They would sit in thoughtful silence, rifle through magazines for inspiration, or simply run off to do something else, planning to return later. For other children, the process was easier and they settled into their work instantly. Regardless of how quickly their work progressed, it was humbling to witness the moment when each child’s idea clicked into place. You could sense the wave of clarity and purpose wash over them as they set themselves to task. They would sift through the huge pile of assorted collage papers and magazines and dig through buttons, cork, sequins, pom pom balls, threads, beads, and other odds and ends to find the perfect color, texture, or imagery to convey their idea.

The students’ approaches to composition varied as dramatically as their themes. Some enjoyed working very flat, while others preferred a more 3D composition. Some students chose clipped images and text, while others wanted to incorporate their own drawings. Some designed beautiful miniature scenes of forests and picnics, while others worked more conceptually and built up layers of interest. Each piece was transformed into a unique and carefully crafted work of art.

The students’ approaches to composition varied as dramatically as their themes. Some enjoyed working very flat, while others preferred a more 3D composition. Some students chose clipped images and text, while others wanted to incorporate their own drawings. Some designed beautiful miniature scenes of forests and picnics, while others worked more conceptually and built up layers of interest. Each piece was transformed into a unique and carefully crafted work of art.

After the last student finished, I packed up all of the supplies and took everything home to (literally) put the pieces together. As I assembled the individual pieces into a finished collage, I was amazed by how well the variety of themes and designs worked together. Thirty-seven distinct responses to a single question had morphed into a microcosm of our beautiful, crazy modern world. Elements of nature (birds, oceans, trees) wove through interpretations of social life (family, friends, holidays) and modern living (technology, medicine, Disney). The Upper Elementary class project about sustainability had become an ecosystem of gratitude and hope for the future, where nature merges seamlessly with people, technology, and traditions: very much like a day at Greensboro Montessori School!

About the Author

About the Author

Gina Pruette is a parent and regular substitute teacher at Greensboro Montessori School. In addition to her commitment to the School, Gina is an active volunteer within the greater Piedmont Triad community where she leverages her expertise in marketing and events planning, fundraising, and tech solutions to further the missions of various nonprofit organizations. Gina recently completed Racial Equity Training through the Racial Equity Institute to strengthen work with diverse populations, and she holds a bachelor of arts from the University of Pennsylvania.

Greensboro Montessori School's mission is to nurture children to be creative, eager learners as they discover their full potential and become responsible, global citizens.