Valid and reliable scientific research and brain development theory should be the driving force behind any school system.

Sadly, in our country, that is too often not the reality. Too many of our nation’s schools are based on an industrial-era, conveyor-belt, “information-in, information-out” style. Missing in this antiquated approach is the child as an agent and the child as an engaged, responsible, and confident citizen and leader.

We are incredibly fortunate that this is not missing at Greensboro Montessori School. We are fortunate that our pedagogy, our methodology, and our very way of learning, thinking, and being are based in sound scientific theory and research. Dr. Maria Montessori saw to that.

Maria Montessori was a scientist. She was a physician, educator, feminist, barrier-breaker, and innovator who utilized scientific observation and experience working with young children to design learning materials and a classroom environment which foster a child’s natural desire to learn. Dr. Montessori opened her first school (Casa dei Bambini) in 1907, and today there are close to 4,000 certified Montessori schools in the United States and about 7,000 worldwide. She developed a school movement that is perfectly in-line with what modern science and today’s neuroscience research confirm our children need.

Even though the field of modern neuroscience and brain research did not exist during her time, her theories and methodologies have withstood the test of time, and today neuroscience and brain research fully support the Montessori methodology. Our recent professional development visit with Dr. Steven Hughes brought together the worlds of Montessori schooling, brain development, and research. Dr. Hughes is a board-certified pediatric neuropsychologist and past president of The American Academy of Pediatric Neuropsychology. His research interests are on what promotes the growth of executive functions, social-emotional skills, and moral reasoning. Additionally, he and his wife have had a longstanding relationship with Montessori: she is an Association Montessori Internationale (AMI) trainer throughout Europe, and Steve is the founding chair of the Association Montessori International Global Research Committee. Adding Steve’s voice to our ongoing dialogue about how we can provide the best Montessori experience possible was exceptionally valuable to us. Over two full days, we had affirmations of what we do, challenging conversations, new inspirations, and reinvigorated aspirations.

Steve framed many of his remarks around what research has shown students really need for success in life. Yes, good grades on tests are helpful as they create access to future opportunities, but good grades on tests alone are not the most important thing. Research shows they are not correlated with success in life, and they are not what companies like Google, IBM, and Ernst & Young look for in new hires. These companies want individuals who can analytically solve difficult problems, who can work collaboratively within a group, and who can leverage complexity. They want people who can look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it. They want original thinking ... conventional schooling is not aimed at helping students develop original thoughts. Montessori schools, on the other hand, are absolutely set up to elicit and generate original thinking.

What students do need to succeed are the underlying neuro-structures of their brain to be fully developed and finely tuned. Dr. Hughes talked to us about how this all happens in the neocortex, the skin of the brain: the neocortex has the area of a linen napkin unfolded and is just a few millimeters thick. In there are at least 6 layers of interconnecting neurons that are extraordinarily complex. And while you may think our neocortex is for “thinking,” really it’s to build a sensory-motor map of the world and to manage sensory inputs, sequences, and patterns. For example, when we sit on a chair or drive a car, we don’t actively “think” about it, as we have a sensory-motor map of those processes and have built within our neocortex perceived expectations of how something like a chair or car works. When we learn how to respond to existing patterns and how to manage anomalies - that’s how we get good at things. It takes practice. As Jeff Hawkins writes: “Patterns are the fundamental currency of intelligence.”

This model of a cortical homunculus illustrates how our brain perceives our hands as the body's primary receptor of sensory motor input.

The way we build those sensory motor sequences which are stored in the neocortex and are the foundations of all that we do when we’re reflexively thinking (or non-thinking) is by doing things. This is the neuroscientific explanation and defense of experiential education. Dr. Montessori knew this, and it makes sense that she is known by many to be the “mother of experiential education.” As Dr. Hughes puts it, “We are human doings, not human beings.” This picture is of a cortical homunculus in The Natural History Museum of London. In layman's terms, it is a model of how our brain perceives our own bodies -- the hands are the mechanisms for receiving sensory input so they are the single most valuable body part to the neocortex. We survive in the world by manipulating the environments around us - it is our skillful interaction with the world that defines us and allows us to be successful. To find this success, we have to build the neocortex. And to build the neocortex, we have to practice doing things; and we have to develop the mechanics and apparatus so the brain knows how to do new things. Practice is how our brains build themselves. That is what Montessori does. All our lessons in motor skills, self regulation, language, math, and sensorial input are presented in individual, sequential ways which build upon previous knowledge and previous sensory motor patterns. This is how we develop the brain, and how our students find success in both school, and more importantly, throughout their lives.

Dr. Hughes reminded us that Montessori education is based on children having “effortful, motivated, repeated, trial-and-error, experimental interactions with the environment.” That’s what happens in our school every day. It’s what empowers our students to find tremendous success in their school settings at Greensboro Montessori School, in high school, and college. While the focus of Dr. Hughes’ talk was not how the Montessori methodology promotes traditional academic success success, it is part of the story because helping children optimally develop their brains helps succeed in life, which includes school.

Dr. Hughes told us, “when we are talking about a well-constructed constructor, we’re also really talking about IQ.” One pretty good definition of intelligence quotient (IQ) is the ability to construct new sensory-motor couplings. Children who are able to fully develop their neocortex have well-developed sensory-motor maps and are able to best make sense of anomalies and new patterns, and thus solve difficult problems.

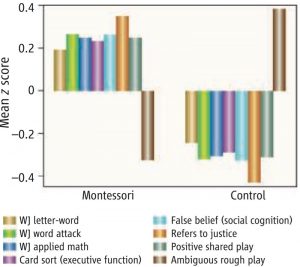

We see these benefits throughout Montessori, and they are documented in Angeline Lillard’s classic Montessori study which was published in 2006 in the journal Science. Through measuring IQ with the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities and studying randomized groups of students in and out of a Montessori program (with an experimental control group), Lillard found Montessori students performed better than non-Montessori peers by nearly a half standard deviation. The best standard deviation improvement from an educational intervention is about a quarter standard deviation; the change of nearly half a standard deviation is monumental.

Lillard's 2006 study found that Montessori students outperformed non-Montessori peers by nearly a half standard deviation in several areas.

It’s also important to remember that scoring well on tests and doing well in school is not necessarily what predicts success in life. We’re not saying school isn’t important, but we are saying success in school shouldn’t be seen as the end result. School success is important because it gives access to future experiences and opportunities. More important is that when your child goes to a school like Greensboro Montessori School, they learn the ability to look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it -- this skill allows them to not only be successful at school, but most significantly, it allows them to be successful in life.

In addition to his fundamental point that experiential education and the Montessori methodology allow students to effectively develop their neocortex and to find success, there were several other key takeaways from our two days with Dr. Hughes. In the various discussions we had, many of the ideas applied to what we can do at home as parents and in the classrooms as educators.

Let the constructor construct.

By taking a neuroscience look at learning, we know that when our youngest children are engaged by doing physical things in their learning, their neocortex in their brains are actively being constructed -- this construction is hard work and requires uninterrupted, child-driven, large blocks of time. Let the constructor construct.

Do not overpraise the child.

Too many parents in our culture praise and overpraise children - sometimes for the simplest of accomplishments. Dr. Hughes reminded us that overpraising children can have negative effects. Research has shown that evaluative feedback (like grades and praise) can stop growth. Dr. Montessori reminds us, “Praise, help, or even a look, may be enough to interrupt him, or destroy the activity. It seems a strange thing to say, but this can happen even if the child merely becomes aware of being watched.” Dr. Steven Hughes jokes with us, “Parents need to really take a good, hard look at your bizzare, irrational, and unnatural desire to praise your children for breathing. Not only does this praise disrupt the child’s concentration, but this evaluative feedback does no good for the developing brain.” While coaching with specific feedback on how to do a task can be valuable, blind praise is not. Again, let the constructor construct.

Never do for the child what they can do for themselves.

Children can often be more capable than we let them be. In Montessori, we are careful to allow the child to do their own work, rather than us do it for them, be it complex math problems or putting on a jacket. We challenge parents to do the same. We do so, because we know from Dr. Hughes that doing and practicing their work allows them to appropriately develop their brains. Yes, it may take more time and patience from us as parents, but let the children do their work -- it’s one of the ways they build their brains.

Montessori does executive functioning very well.

Executive functioning is what we do with our IQ below the level of consciousness – how we organize, make sense of, and make discernments in order to execute and make decisions. From the neuroscience perspective, this is called cognitive flexibility and is an important part of executive functioning: when Plan A doesn’t happen, we have to have the flexibility and adaptability to create Plan B. Executive functioning is developed when the neocortex is allowed to develop those sensorial-motor maps through repeated practice and doing.

Concentration is fundamental to Montessori.

Classrooms at Greensboro Montessori School are based on giving children time to concentrate. Too many other school systems shuffle children from one idea or class to another every 34 minutes. From the neuroscience perspective, Dr. Hughes told us that concentrating is engaging the frontoparietal network in effortful cognitive tasks, where rules or information learn to be utilized and to guide behavior. Dr. Montessori knew that “Concentration is the key that opens up the child to the latent treasures within him.” Once again, her methods developed over one hundred years ago are today confirmed by modern neuroscience research. This concentration is how we develop capacity and capabilities to link together all our future skills and ultimately succeed in a complex world. It’s the foundation for us to learn how to look around, figure out what needs to be done, and do it.

Never interrupt the concentrated child.

Children innately want to explore, to touch, and to engage in certain types of work or projects. At various parts of their developmental journey, they are drawn to different things. And it is nature’s design that they want to do some work, or age-appropriate activities, again and again. Somehow, they know they need to practice them. And through modern neuroscience, we now know very well that this practice of building sensory-motor maps in the brain is one of the ways the neocortex develops within the brain. We know this is the foundational building block for future thinking. And through research and brain scans, we know that when the child is actively working and concentrating, they are literally building their brains.

When this is happening, this brain building, there is nothing we can or should do. We need to step back, let the child direct, and let the child be inspired. Never interrupt the concentrated child; it is then when they are constructing. In a Montessori classroom, we build time and systems to allow children to find real concentration and to focus on big work. While they aren’t able to work on one project or subject the entire day as there are other lessons and other parameters for the day, we do pride ourselves in having blocked times (sometimes as long as three hours), where the children can focus on their work and consequently develop their brains. As parents, we should work to not interrupt a focused and concentrated child; while a quick picture, a redirection, or new idea from us may be so tempting… try to resist that urge, knowing that concentrated work is very important, that our children are literally developing their brains.

For two full days, Dr. Steven Hughes toured out school, and engaged with our faculty, our students, our parents, and our administration. When he stepped away he wrote to us: “I can tell you are heading into one of those wonderful chapters in an organization with the right people are on the bus, and the bus is headed in the right direction. One can’t always force those conditions but when they are present amazing things can happen. I’ll look forward to hearing about the amazing things happening at Greensboro Montessori School in the future!’

There is something incredible happening at Greensboro Montessori School!

That “incredible” lives within the people and the work our students do every day; that “incredible” permeates our culture and the program. When any of us answer the question, “Why Greensboro Montessori School?”, this “incredible” is most likely part of our answer. We intuitively and deeply know there is extreme value in a Greensboro Montessori education. We know that the School both nurtures and pushes our children; loves and empowers them. We know that our children are learning to think critically and originally, to look beyond polarizing black and white perspectives, to lean into complex and difficult ideas, and to work effectively, eagerly, and ethically within a team. We know that there are some of the best teachers in the entire state of North Carolina caring for our children every single day. We feel this.

While we all know these things to be true, our team has been working on providing families with data points that answer this question (Why Greensboro Montessori School?) in a more analytical fashion. In our reenrollment packets, you will see some of the quantitative data we have been gathering. You’ll see data that tells you the average ACT score in North Carolina is 19 and our college-aged alumni’s average is 30. Or that our students’ English composite scores on our standardized tests is in the 92nd percentile nationally. Or that 88% of our students feel like they were very well prepared high school.

In addition to quantitative data like this, there is also important qualitative data that answers this same question. Some of the best qualitative data comes from our alumni students and families. At our recent Grow With Us event for each of our students and families who will transition into a new division in the fall, we invited two of our alumni parents, Nancy King Quaintance and Dennis Quaintance, to reflect on why they kept their two college-aged children at Greensboro Montessori from toddler through to graduation. Below are a few excerpts from their remarks:

[dt_sc_pullquote type="pullquote1" align="center" icon="yes" textcolor="#81d742"]The thing that kept bringing us back and causing us to know that Greensboro Montessori School was the place we wanted to be can be summed up in one phrase - a loving community. We felt like our children were understood and appreciated for who they were.[/dt_sc_pullquote]

[dt_sc_pullquote type="pullquote1" align="center" icon="yes" textcolor="#81d742"]Another thing that brought us back is that we believe that for any organization, to really function to its potential, it has to have a compass and a sense of north. And every time we were in a [parent] conference whether it was with Doug or Jonathan in middle school or with the Primary teachers, without it being scripted, [the teachers] would say 'this is happening because its part of the idea of children being eager learners and discovering their potential to become responsible global citizens.' It makes me want to cry because imagine if we could do that as a whole global society.[/dt_sc_pullquote]

Those qualitative data points spoken by alumni parents who were at our School for 12 years can help inspire those of us who have had children at the School for only one or two years. Perhaps even more inspiring, though, is listening to their college sophomores reflect on their journey at Greensboro Montessori School. Please click on the link below to hear why they loved their time with us:

Finally, one more type of answer to the question, "Why Greensboro Montessori School?", comes from scholarly research. Dr. Maria Montessori herself was a scientist. Her methods and practices were all based on known science about human development and student learning. Educational scholars and practitioners are also always reflecting on and researching the Montessori methodology.

A 2012- 2016 Longitudinal study involving 43 Montessori Programs was recently published by the Riley Institute at Furman University. One of their conclusions was “a higher percentage of students in Montessori programs met or exceeded state performance benchmarks in language arts, math, science, and social studies, and showed faster growth in language arts over the course of the study.”

And if you need one more answer, it’s because it’s what we ultimately want for our children. We want them to be successful, well-adjusted, confident, competent, and creative people. And we know that Greensboro Montessori School can help them become just that.

Really, what more could we ask for?

"The willingness to show up changes us. It makes us a little braver each time." - Brené Brown

I think Brené Brown and Maria Montessori would be fast friends, had they lived during the same time. They both believe deeply in showing up as who we are … and in following that authentic self. Montessori calls it following the child; Brown calls it being authentic and vulnerable in order to find wholehearted living. It’s important to say that the concept of “vulnerability” has evolved into a positive and beneficial behavior and characteristic in both Brown’s and my research.

Montessori wrote that “the child is capable of developing and giving us tangible proof of the possibility of a better humanity. We have seen children totally change as they acquire a love for things and ideas and as their sense of order, discipline, and self-control develops within them.... The child is both a hope and a promise for all humankind.” A hope and promise for humankind starts at the center of the child’s ability and gift to show up as who they are. If this concept interests you, I thought I’d walk you down a path of Brown’s research, and why I think it ultimately connects to our work at GMS.

Brown began her research journey in the field of social work with her basic belief about the necessity of human connection. “Connection is why we’re here; it is what gives purpose and meaning to our lives” (Brown, 2012a, p. 253). Her dissertation explored assessing relevance in professional helping (e.g., pastoral care, psychologists, educators, or organizational leaders). Over six years, she interviewed 1,280 professionals to develop her theory of accompaniment.

Through asking her participants about human connection, she ended up developing the related ideas of shame and shame resilience. Asked about human connection, participants invariably ended up talking about instances of heartbreak, betrayal, and shame, which Brown defined and coded as the fear of not being worthy of real connection. That emerging pattern led her to return to her data to investigate why and how some were resilient to this shame, heartbreak, and betrayal. She eventually developed a model of shame and shame resiliency, which revolved around empathy, courage, compassion, and connection. The patterns in her data pointed to wholeheartedness, which Brown developed into what she called wholehearted living. And from her study of wholehearted living, Brown then focused her research attention on the power of vulnerability. Vulnerability and having the courage to show up authentically and humbly as who we are connects to how we ask our students at GMS to show up. Brown (2012a) wrote, “Vulnerability is the core, the heart, the center, of meaningful human experiences” (p. 12). Vulnerability (being open, authentic, and humble) directly connects to a person’s ability to honestly know their self and their limitations.

Here is where we begin to connect more to the work we do at Greensboro Montessori School. We believe, just as Maria Montessori, that we are always striving for meaningful human experiences and lessons. To achieve this, we need to empower our students to think independently, critically, and openly. And that takes courage.

To be comfortable with their personal vulnerability, Brown writes that people must first have a strong sense of love and belonging. We work to instill that belonging everyday in all our classes. That sense of worthiness is a foundational path for students to find greatness. Conversely, when people cannot be real and honest, i.e. vulnerable, they block great ideas and innovation. Brown (2012a) identifies a lack of vulnerability as the “most significant barrier to creativity and innovation” (p. 187). This lack of vulnerability fosters a fear of change and close-mindedness. If we cannot empower our students to take safe risks and to see the value of struggle and failure, then we may be stinting their ultimate growth.

It takes courage and bravery for students to have new ideas and try new things. Entrepreneurship, growth, and new ideas cannot thrive in an environment that does not welcome openness and authenticity. One participant in an interview with Brown (2012a) said, “When you shut down vulnerability, you shut down opportunity. By definition, entrepreneurship is vulnerable. It’s all about the ability to handle and manage uncertainty” (p. 208). Entrepreneurship thinking and habits of mind is something we pride ourselves on at GMS.

And as for how we create a culture that welcomes these ideas of vulnerability, true courage, and entrepreneurial thinking, school research is crystal clear that we need adults in schools (leaders and teachers) who are willing to display and model this open sense of courage in a quest for better understanding and learning. The adults must first have the courage and wisdom to intentionally be vulnerable. As an adult learning community of about 60 employees, we work everyday to be open to ideas, as we mindfully and intentionally follow the child. I also invite each of our parents to intentionally join us on that journey as we partner to help empower our young people to be confident and inspired to display the sort of courage that Brené Brown writes about.

I’ll leave you with a final thought from Brown. While the quote is specifically about leaders, I think applies all the same to us as parents, as teachers, and as human beings:

“Across the private and public sector, in schools and in our communities, we are hungry for authentic leadership – we want to show up, we want to learn, and we want to inspire and be inspired… When leaders choose self-protection over transparency, and when self-worth is attached to what we produce, learning and work becomes dehumanized… Re-humanizing work and education requires courageous leadership. It requires leaders who are willing to take risks, embrace vulnerabilities, and show up as imperfect, real people. (Brown, 2012a, p. 5)

Have a great and courageous weekend.

- Kevin

Works Cited

Brown, B. (2002). Accompanar: A grounded theory of developing, maintaining, and assessing relevance in professional helping (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Texas, Austin.

Brown, B. (2010a). The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are. Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Brown, B. (2012a). Daring greatly. New York: Gotham Books.

Brown, B. (2012b). Vulnerability and inspired leadership. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Leadership Series.

Montessori, M. (Published 1992). Education and Peace. The Clio Montessori Series.

Click here to check out a whole host of books and audio published by Brené Brown

What do the oldest fabric in the world and a vintage typewriter have in common with my dentist? And what do they have to do with art? Well, I encountered each of them in the course of one week, and the intersection of these seemingly disparate things gave me an “a-ha” moment about the symbiotic relationship between creating with technology and hands-on art making in our School’s art studio.

As a mixed-media artist, I am naturally drawn to tactile, malleable, hands-on materials and adore using these materials in my lessons. If you walk into Greensboro Montessori School’s art studio, you will see a variety of rich textures, fibers, paints, clay, found objects and nature. You will also find a technology wall where one of the School’s 3D printers, a computers and iPads live. These two worlds co-exist harmoniously in our art studio and with each new day I am learning and teaching how technology and art are interwoven and applied in the world beyond the studio.

For instance, many Greensboro Montessori School faculty recently participated in an excellent coding workshop from Code.org. During this workshop I learned how coding is fun and creative and identified a great way to apply this technology in my classroom. Once armed with coding knowledge, students can practice their skills by writing an algorithm resulting in a specific design being drawn on their computer. They can bring this code to their art lesson and exchange it with another student. From there, students run each other’s algorithm to see if it produces what the creator originally intended.

Another project where technology and art intersect is stop motion animation. Students use a stop motion app on our classroom iPads to tell stories, but they also use physical objects make stop-motion animation the good old-fashioned way (by moving an object in small increments, taking photos of the object after each movement, and viewing multiple photos per second in a continuous sequence to create the illusion of motion). One of the most famous stop-motion animation films is the 1964 television special, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. In our classroom, students manipulate KEVA planks, not wireframe figurines, to make their movies. The excitement has been great, and upper elementary students often rush back to class to ask Cathy Moses to come see their work!

Middle school students have been very helpful in teaching upper elementary students about the School’s 3D printer and 3D drawing program, SketchUp, which brings me back to my “a-ha” moment about the connection between art and technology. Within the course of one week at school I led a felting project demonstrating how to create with the oldest fabric in the world and guided lower elementary students in a freedom of speech exercise where they used a vintage typewriter to create art with their own words. I was reminded how each of these discoveries represented a technological shift at the time of their invention. At the end of the week, I went to the dentist and experienced a modern technology and art revolution in the making.

As crazy as it sounds, and as personal a story it is, my time at the dentist was real-world affirmation of the integration of art and technology. I was scheduled to get a crown and had anticipated my visit being the first of two required to complete the procedure, but then I was introduced to CAD/CAM (computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing) dentistry. While I was in the office, my dentist used technology to capture a 3D rendering of my tooth (CAD) and reproduce it onsite with a grinding and milling machine (CAM). While the grinding process used in my dentist’s office is different from the fabrication method used in 3D printing, the use of technology to produce sculpture in both cases highlights the inspirational interplay between technology and art. (And to top it all off, my ceramic crown was fired and glazed onsite, just like our students’ pottery is fired and glazed in our kiln!)

As we continue to create with our hands in collaborative and productive ways in Greensboro Montessori School's art studio, we will continue to grow the use of technology as well, because technology helps strengthen the development of our students 21st century skills and introduces them to career opportunities where art and technology co-exist.

This summer I've been introduced to Montessori Market, a summer camp Greensboro Montessori has offered for the last 17 years. Through a unique blend of environmental education and hands-on learning, campers participate in a week-long business preparing consumer goods for sale to the general public at the conclusion of camp. Just as our 2016 graduating class impressed me, Montessori Market has revealed yet another School tradition which is so much more than meets the eye.

Montessori Market is an all-hands-on-deck camp featuring contributions from the entire school community. Whatever produce we can't harvest from our own permaculture gardens, we source from local farmers. Both faculty and students work together to gather ingredients before camp even begins. This year, Nancy Hofer, Mary Jacobson, Kristy Ford and Andi Bogan chaperoned our Lower Elementary Al Fresco summer camp students to a local blueberry farm where they hand picked blueberries for jam. We also needed peaches which led me to think about The Produce Box, a service which delivers fresh produce from North Carolina farmers to my doorstep each week. After one quick trip to Raleigh and the overwhelming generosity of The Produce Box, we had boxes of peaches, certified organic zucchini, green bell peppers, corn, jalapeños and tomatoes.

The students began camp with a full refrigerator of fresh, North Carolina-grown produce and three sprawling gardens from which to pick fresh basil for pesto and lavender for sachets. They have also made a wide variety of handmade crafts to accompany their foodstuffs.

As the students approach the end of the week, the most beautiful and compelling aspect of camp comes alive. With finished goods ready for sale, you have to wonder, "for whom and to whom will they sell their goods, and where?" I've since learned that Montessori Market has always worked for the benefit of children in need. Campers wake up bright and early to sell their products at the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market on the Saturday immediately following camp, and all proceeds are donated to a charity focused on kids. Hence, it's time to introduce BackPack Beginnings.

Founded six years ago by Parker White, a new mother at the time, BackPack Beginnings' mission is to deliver child-centric services to feed, comfort, and clothe children in need in Guilford County. By ensuring food and basic necessities are given directly to children in need, BackPack Beginnings makes a positive and lasting impact on their health and well-being. As a 100% volunteer organization, BackPack Beginnings serves over 6,000 children experiencing hunger and trauma in our community annually. Recently, Parker has been named one of four finalists for The NASCAR Foundation’s Sixth Annual Betty Jane France Humanitarian Award presented by Nationwide. This award honors incredible volunteers from across the country who have made a profound impact on children’s lives in their community. (You can vote for Parker daily from now until September 26; if she wins, The NASCAR Foundation will make a $100,000 donation to BackBack Beginnings.)

Our Montessori Market campers have been learning, cooking, and collaborating on behalf of BackPack Beginnings all week. This Saturday, July 30, they will be at the Curb Market proudly displaying their finished goods, and a donation to BackPack Beginnings will allow market-goers to shop from their products. In addition to the pesto and sachets, shoppers may also select from blueberry jam, peach jam, salsa, zucchini bread, and a number of homespun crafts.

Peach and blueberry jams—lovingly made by students participating in Montessori Market—ready for display at the Greensboro Farmers Curb Market.

100% of the donations received on Saturday will assist the BackPack Beginnings' Food BackPack Program which helps fight childhood hunger in our community by filling the weekend food gap for children in need. By the numbers, this program sends 1,600 children from 26 schools with fresh food each weekend totaling 6,400 food bags per month. This effort is in addition to their Comfort BackPack, Food Pantry and Clothing Pantry programs. While our hope is that we receive enough donations on Saturday to empty our booth, any remaining products can be directly donated to BackPack Beginnings for direct inclusion in Food BackPacks or the Food Pantry.

So this is the story of how a summer camp evolves into so much more than a summer camp. How the Montessori philosophy challenges us, as adults, to push our kids to do more than text, snapchat and Netflix during summer break. How engaged faculty and community organizations prepare children for a lifetime of success by providing real-world experiences in running a business, manufacturing, time management, and philanthropy. And how children come together to help others less fortunate than themselves. And how Montessori Market is more than meets the eye.

My first day at Greensboro Montessori School was Tuesday, May 31, which was also the day of our Council of Elders interviews with our graduating middle school students. The week that followed was a crash course in the rich experiences exclusive to our students contrasted with the universality of adolescence…and most notably, the extraordinary academic and social accomplishments of students who have learned under the Montessori method of child-led education.

As I walked to Susana D’Ruiz’s Spanish classroom for my Council of Elders interviews, I quickly noticed how comfortable I felt in our middle school hallways. Down the main corridor, one side was lined with lockers, a familiar scene from any middle school in the country. And as I met with the interviewing graduates, I was immediately transported to middle school years when each moment swung along a pendulum between my own teenage angst and hubris.

But this group displayed a wealth of life experiences I never knew at 14:

- They had run their own businesses during Greensboro Montessori School’s holiday marketplace, not once, but three separate times in each of their years in middle school. This repetitive format allowed them to learn and improve their business acumen from one year to the next.

- They had traveled extensively studying U.S. government in Washington D.C.; visiting Biosphere 2 in Oracle Arizona; participating in the United Nation’s Global Citizen Action Project in New York City; and living with host families from The Summit School in Costa Rica.

- They had cared for a baby (albeit, a mechanical one) for a weekend, with dashed hopes of sleep as they tried to determine whether their baby needed to be changed, burped, fed or rocked. Any many had to pay their parents to babysit in order to maintain extracurricular commitments in sports and music.

- They had completed an introspective “Who Am I” project which had unlocked a fresh sense of confidence and creativity as they prepared for the leap to high school.

- They lived Survivor-style at Greensboro Montessori School’s 40+ acre Land Lab where they cooked their own food, slept in shelters built by students and hauled their own fresh water. Divided into tribes, they experienced life without electricity and gained a deep appreciation for social and environmental responsibility.

But the graduates’ accomplishments extended well beyond these experiences, a point that came full circle for me when I attended their graduation ceremony.

The three-and-a-half-hour celebration featured heartfelt, personal introductions of each student from a faculty member of the graduate’s choosing. After each introduction, the respective graduate gave a speech. This combination – faculty introduction and graduate speech – repeated itself sixteen times yet was never boring or monotonous. It was deeply revealing about the extraordinary bond that results when faculty invest just as much heart and soul into their students as their students put into their work. The result of faculty who understand their students’ so well that they enable each one to reach his or her full potential.

And the academic results are astounding:

- Two of our graduates will attend the Early College at Guilford, which U.S. News and World Report just ranked the top high school in North Carolina, and they only accept 50 new students a year. When you look at the numbers, Guilford County Schools has 23 middle schools and a host of other private schools. With 16 eighth graders, Greensboro Montessori Schools represents a fraction of a percent of eighth grade enrollment in this county, but we represent 4% of the Freshman class at the best high school in the state.

- Five of the graduates will attend the Weaver Academy for Performing and Visual Arts where they will follow a “rigorous curriculum comprised of Honors and Advanced Placement courses” while also following a “specified course of study in their performing and visual arts area of concentration.” One of our graduates will concentrate in dance. Another in music – the drums specifically, and yet another in visual arts. The other two were accepted into the music production concentration, open to only nine new students a year.

- One of the graduates will attend Rabun Gap-Nachoochee School, a college preparatory day and boarding school with a “100% college acceptance rate and placement includes the nation's most selective institutions including Harvard, Princeton, Duke, Brown, and Emory as well as highly regarded colleges and universities both domestic and abroad.”

- Four of four graduates who will attend Grimsley High School were accepted into the International Baccalaureate (IB) Programme, a course study known for academic excellence, rigor and achievement. Students who graduate with an IB diploma often enter college with advanced standing from course credits earned in high school.

This list highlights just over half Greensboro Montessori School's Class of 2016. In all, our graduates will attend eight distinguished secondary institutions including those listed above and the American Hebrew Academy, Bishop McGuinness, Northern Guilford High School and Salem Academy.

As I begin to settle into my new role, I’m humbled by the success of these young adults 20 years my junior and feel a deep responsibility to shine a light on this magical place. A place where academic brilliance lives concurrently with Montessori methodology, two concepts that many mistakenly, and for us Montessori educators, might I add painfully, assume are mutually exclusive.

This summer, two of our Middle School faculty, Deirdre Kearney and Jenny Kimmel, attended Montessori teacher training at the reknowned AMI Montessori Orientation to Adolescent Studies located in Huntsburg, OH on the campus of the Hershey Farm School.

Deirdre joined GMS in 2007 and teaches Humanities in the Middle School. Jenny joined our faculty as an intern with our gardening program in 2003. She is the director of the environmental education curriculum at GMS and oversees the GMS Land program in Oak Ridge.

The AMI Orientation to Adolescent Studies offers an overview of Dr. Montessori’s approach to adolescents within the whole framework of human development. By exploring Montessori theory in depth, the participants will come to understand the contribution of the third plane of development (12-18 years of age) as crucial to the development of the individual and will be significantly prepared to aid development during this important time of life.

An important part of the orientation is to experience the life of the adolescent: their studies, their practical work, their community life, their growing need for independence, and their need to work side-by-side with adults. Through time spent in the prepared environment of the farm, participants explore this need for independence and an awareness of human interdependence, both of which become concretely realized and internalized in Montessori adolescent communities that genuinely provide a “school of experience in the elements of social life.”