Liz Haff joined us this year after a 25-year teaching career in Maryland, where she also served on several committees focused on parent family connection and student relationships. In addition to her wealth of experience, Liz's academic résumé includes a Montessori teaching credential in Early Childhood (2 1/2 to 6 years old), a Master of Science in curriculum instruction from Western Maryland College, and a bachelor's degree from State University of New York at Binghamton.

Liz partners with Shyla Butler in our Primary 2 classroom. While 2022 may be her first year at GMS, Liz already feels like family. Her warmth and intentionality shine through our interview for this Faculty Spotlight.

GMS: How did you learn about Greensboro Montessori School?

LH: Last school year, I knew I was looking to return to Montessori education. I also found the city of Greensboro which seemed to be everything I was looking for in a place to live. I asked myself: “I wonder if there is a Montessori school in Greensboro, so I typed Greensboro Montessori School into my Google search, and there you were!

GMS: We wish we we could thank our SEO strategy for that perfect Google result, but you guessed our School's name on the first try! What made you choose to join our School?

LH: Greensboro Montessori School basically swept me off my feet. I discerned it to be a heart first school, and one in which I very much want to be a part of now.

GMS: We're so happy you're here. You’ve spent the last several years teaching elementary students, yet you've chosen to join our Primary team. What do you love about Primary-age students?

LH: So much. Mostly it’s the openness that I most love about this age. Every time I meet and become friends with people in the age group of 3-6 especially, I feel as if I am communicating with people who are awake: interested in learning, curious about the world, and in love with life.

GMS: You just reminded anyone who knows a 3- to 6-year-old how magical this age truly is. Now that we know why the age group inspires you, what is it about Montessori that you love?

LH: Choice, for sure. I am sort of obsessed with choice. It is such a wonderful experience for humans to choose what to read, think, touch, see……. It is our ability to choose that helps define us and create us. I believe in providing choice to students and watching how they respond.

GMS: What are you excited to learn from your students, and what are you excited to bring to them?

LH: I am looking forward to getting to know a new group of people: their likes and dislikes, what makes them laugh, and how I might help them better navigate their world. I will bring respect to them: for how they see the world, and how I might help them learn from it.

GMS: It's hard to change topics after that answer, and we have to know: did anyone else move with you from Maryland?

LH: My husband Tom and our dog Darby (pictures below) moved to Greensboro with me. It has been a great adventure already as we explore the Greenways together, and the little eateries.

GMS: Do you have your own children?

LH: I do! Yay! I have three Montessori children! They are all adults now pursuing their passions in the world. Jim lives in Atlanta and is a martial arts instructor and a musician who performs every weekend in Macon, Georgia! Andrew is my second born son who is a middle school history teacher who teaches in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He is a Fulbright scholar who taught in Vietnam for a while. He loves harping and singing as hobbies when he is not teaching. My daughter Caitlin is an attorney who attended NYU in New York City. We are great friends and our favorite thing to do is laugh together and be silly.

GMS: We can't wait to meet them! Now, it's your turn to tell us more about you. What are your hobbies?

LH: I love writing, I blog regularly. I love laughing. I have enjoyed singing since I was very young, and I have been a member of many singing groups. Darby and I love to walk the greenways and admire the trees of Greensboro.

GMS: I overheard our director lower school, Missy McClure, mention a faculty and staff talent show recently. Maybe we could all hear you sing one day. In the meantime, it’s a Friday afternoon, and you need a pick-me-up. Do you reach for a salty snack or a sweet treat?

Sweet and salty treats are awesome. I also adore peaches and olives.

GMS: Of all the places you’ve traveled to, what is your favorite destination and why?

LH: My most favorite place is the beach, and Wrightsville Beach in North Carolina in particular. I used to love riding the waves over and over again. Now I love to take my chair down to the water’s edge and dream my dreams.

GMS: If you could travel anywhere you’ve never been before, where would it be and why?

LH: I would like to go to all the toy stores in the world, especially ones where a lot of the toys are out to touch and not wrapped up in plastic.

I also want to see Lake Superior with my daughter-in-law Katherine. I love wild natural places, with hopes of seeing wild animals.

GMS: Okay, so the next toy store you have visit is Toys & Co. in Greensboro. We think you'll have tons of fun. Speaking of fun, what is one fun fact about you that we wouldn’t learn about you without asking?

LH: I have a twin brother whom many people call Uncle Jim. I adore him, and he makes me laugh more than anyone in the world. He wrote a play and it had a debut in New York City for a week! When we were in high school we performed in "Mame." I was Mame and he was my nephew, Patrick. That experience was Awesome!!!!!

GMS: Other than Dr. Maria Montessori, who would you like to meet from history and why?

LH: I would love to meet Frederick Douglass because I am so inspired that he taught himself to read when he was young. I am impressed by Great Ideas and anyone who can express themselves in writing well!

GMS: We have adored this interview. Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

LH: I am very happy to be a part of Greensboro Montessori School. Everyone I have met is encouraging, kind and joyful. I know this is where I am meant to be.

GMS: In concluding out interview, we realize we didn't ask you about your extensive volunteer work. We know how humble you are, so we're going to share for you. While working in Maryland, you supported both your local community and those from afar. You raised $1,500 for tsunami relief for people in Indonesia in 2018, and during the height of pandemic, you and Tom assembled 100 care kits filled with toys to help children experiencing trauma. (We used the picture you shared with us from this work as you blog's header image.)Thank you for your caring and generous spirit.

Beth Wilson will join our Upper Elementary teaching team this fall. Beth has spent the last 20 years at a Montessori school in Minnesota. She also has a decade of experience training Montessori educators at the Center for Contemporary Montessori Programs at St. Catherine's University in St. Paul, Minnesota. Beth earned her Master of Arts in Education with a focus on Montessori studies from St. Catherine's and her bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. She holds multiple Montessori teaching credentials spanning the totality of Elementary and Adolescent education (ages 6 to 18).

As Beth enjoys her last summer in Minnesota, we wanted to get to know her better in anticipation on her arrival. We recently spent some "digital" time with her learning more about her passion for Montessori education and her favorite flavor of ice cream. Here's our interview:

GMS: How did you learn about Greensboro Montessori School?

BW: I wasn’t actually looking for a new teaching position. I was casually browsing the Montessori Jobs group on Facebook, and a few clicks later I came across the job post on the American Montessori Society's [AMS] website. After reading the job description, I knew that I had to apply. It was like fate.

GMS: As an AMS-accredited school, we love that you found us through AMS. Why did you ultimately choose to join our School?

BW: After getting to know Kevin, meeting the staff, and spending time at the school, I knew it was the right place for me. I feel like it’s my “dream school” – the kind of place that every teacher hopes that they get to be a part of in their career.

GMS: We are equally excited to welcome you to our community. What is it about the Montessori method that inspires you the most, that keeps you teaching, learning, and growing in this pedagogy?

BW: I love the freedom to follow sparks of interest, that there is time to explore ideas and curiosities. I also love the interconnectedness of the Montessori curriculum: rather than each subject area being taught as a separate entity, the children learn about how one area cannot exist without another, such as how we cannot have art without geometry or science without math.

GMS: You will join our Upper Elementary division this fall. What is your favorite part about working with Upper Elementary students?

BW: I love the enthusiasm of Upper Elementary students. They are more independent than Lower Elementary students but still so excited about the world. Their imaginations are big and their wonder about how everything fits together is empowering to me.

GMS: Speaking of the students, what are you excited to learn from them, and what are you excited to share with them?

BW: I want to learn all about Greensboro Montessori and North Carolina! I’ve only visited the state once, and that was when I came to spend time at the school. I want to learn all the great places to visit, any cool history about the state, and what they think makes GMS special to them.

As for me, I really want to share my love of animals with the students (my bunny, Hufflepuff, and two leopard geckoes, Pinky and Floyd, are joining us in the classroom), and I have already asked Doug if we can help with the chickens. I also want to share my love of art, and I try to include as much creativity into our lessons as possible.

GMS: So Hufflepuff, Pinky, and Floyd are moving with you from Minnesota. Who else is relocating with you?

BW: My husband, John, and our 13 year old and youngest child, Melanie (pictured below), are embarking on this grand adventure with me. We’re also bringing along our big brown dog, Yoshi and our little kitty, Kasumi (also pictured below).

GMS: The family photo you sent us (at the top of this post) has a lot more people in it.

BW: Yes, that’s my whole beautiful, crazy family. It’s from a few years ago, but it’s the best one I have of all of us. From left to right: My son Zach (24), my husband John, my son Will (21), and my oldest son, Nate (27). Then, it’s me and our daughter, Melanie, who will be joining junior high at GMS.

GMS: We hope to meet the whole fam one day. In the meantime, we'd love to learn some more fun stuff about you. Tell us something about yourself that we wouldn’t learn from your résumé or CV?

BW: Hmm … I’m addicted to Diet Coke, and I’m a sucker for a good donut. Or cookie. Actually, pretty much anything that’s sweet. But not marshmallows. I hate marshmallows.

GMS: What hobbies do you enjoy outside of work?

BW: My husband would say that I have too many hobbies. Reading and drawing are my biggest loves, and then after that, I love quilting. I’m a big sci-fi fan, and although I do love Marvel movies, I’d pick Star Wars over them any day. I love to go camping and take hikes, and my life would not be complete without a horse in it.

GMS: Once you’re settled here, where are you most excited to travel to on the East Coast?

BW: I really want to go to the Outer Banks. "Misty of Chincoteague" was a favorite childhood book of mine, and I really want to see the wild ponies. I also want to see the mountains. We have lots of trees and lakes in Minnesota, but no ocean and no mountains.

GMS: Other than Dr. Maria Montessori, who would you like to meet from history and why?

BW: Oh, there’s so many people I would love to meet, and it’s hard to narrow it down. Jane Austin is a favorite author of mine, and I’ve always admired the art of Franz Marc. I would try not to pester them about their work so much, but rather I’d like to just hang out with them as regular people, maybe hit a brewery or catch a Twins game.

GMS: What is your favorite flavor of ice cream?

BW: Anything with coconut in it. I love the Almond Joy ice cream they have at fancy ice cream shops. If grocery store ice cream is what I’m choosing from, then it’s Breyers vanilla bean ice cream.

GMS: We have some great ice cream parlor's in Greensboro. We'll have to go once you're here. Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

BW: Just that I am so excited to be joining the GMS family! And no, most of Minnesota is not like the Fargo movie, except those snow scenes. Those are pretty spot on.

Greensboro Montessori School's Upper School students took a leading role in Friday's Earth Day celebration. Upper Elementary students kicked off the morning with readings of original poetry and Spanish. After the program (which we shared live on Facebook), Junior High students hosted Lower and Upper Elementary students at eight different different stations set up on the Athletic Field. Each station featured an activity to to raise awareness for Earth Day, including ideas for recycling, composting, and even limiting our waste. Primary students enjoyed a lesson with our environmental educators, Chelsi Crawford and Sara Stratton. Toddler students took everything in from their shaded mats under the trees, just steps away from their play yards.

The original poetry shared by our Upper Elementary students highlights our integrated curriculum. Students combine their skills in English, Spanish, creative writing, science, environmental education, public speaking, and leadership all at once. We are honored to publish their work for all to experience.

Redbud Tree

Lydia, Sixth Grade

The Eastern redbud tree, purple blossoms in early spring. Small beacons of colour adorn the dull, monochromatic landscape. Bursts that spring is just around the corner.

As the blossoms begin to fade, they get swept away by the gusts of wind that spring brings. Petite purple petals pressed onto the ground as they get trampled by tiny feet. But not all is lost, leaves that are a deep crimson, like garnet, or a sharp, zesty lime the size of a hand unfurl. The leaves are shaped like spades. Desperately trying to hold onto their branches by their paper-thin stems. Through treacherous storms they hold on, not falling yet, for the leaves have roots of their own.

The redbud tree is eternally stretching, reaching its roots through the mycelium and soil, while the branches are competing for the warm rays of sunlight. The uneasy cottontail rests by the roots of the tree, protected by the lush canopy from the hungry hawks’ view.

During autumn, the leaves of the redbud tree glow orange, like a campfire. Only turning into a bonfire as the chorus of the other deciduous trees chime in in the early November. Then, the redbud tree goes to sleep as the long, cold winter days begin.

Día de la Tierra Upper Elementary Group A

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque es el único planeta que temenos.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque es nuestra casa y nuestro hogar.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque vivimos en ella.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque hay animales, árboles, océanos y más.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque es la casa para todos los tipos de vidas.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque nos da comida.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque es la casa de todos.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque es muy bonita. Los humanos debemos comprender que no se debe hacer daño a la Tierra.

- Debemos cuidar la Tierra porque o si no nos extinguieremos.

- Debemos cuidar la tierra porque es nuestra protectora y nuestro hogar.

sphagnum

Tanner, Fourth Grade

The sphagnums dance in the rain like an umbrella being twirled. The sphagnums dance in the rain on the mother tree. The sphagnums dance in the rain in the rainforest. The sphagnums dance in the rain under the shade. The sphagnums dance in the rain and the damp mother tree is playing her music. The sphagnums dance in the rain, their spore capsules open up and the spores fly away. The sphagnums dance in the rain as the 10,000 ancestors watch them. The sphagnum dances in the rain, the calm green color is shimmering on as the rain falls on them, the sphagnums dance in the rain; they have no roots, stems, leaves or seeds. The sphagnums dance in the rain, they can grow until they run out of room. The sphagnums dance in the rain in their fuzzy soft coats. The sphagnums dance in the rain. They are used for medicine to save peoples lives. The sphagnums dance in the rain; they get picked and re-planted to make a garden look nicer. The sphagnums dance in the rain.

You may have noticed an unusual orange fruit in your child’s book bag this week. You may even have asked, "what is this?"

Originally from Asia, and morphologically considered a berry, the persimmon is a lovely fruit that matures to a deep orange color in late Autumn. If you’ve ever visited Greensboro Montessori School's Primary Garden, you’ve probably noticed our beloved persimmon tree, planted over 20 years ago by master permaculturalist, Charlie Headington. In the years since, this tree has been lovingly pruned and harvested by our favorite garden coordinator, car line greeter facilities assistant, and student support pal, Aubrey Cupit.

Generations of GMS students share a collective nostalgia for the flavor of the persimmon. To them, it seems a rare, exotic fruit with notes of magic and pure joy only attainable from our grounds. Students begin asking for persimmon snacks in our Environmental Education classes on the very first day of school, and then every subsequent day until we cut into the first ripe persimmon in October. It would be difficult to adequately describe the infectious wave of excitement when our students find out we are having persimmons for snack.

A firm persimmon tastes like a combination of honey, peach, and mango, with earthy undertones and the texture of an apple. For those unfamiliar with this fruit, I would recommend eating it raw, just like an apple, skin and all. Others prefer to bake softer persimmon pulp into pancakes, bread, or cookies. Persimmons work well in savory applications such as persimmon vinaigrette and other meat-based dishes akin to pork and apples. Dehydrated persimmon pulp creates a delicious fruit leather, while dehydrated persimmon slices make an excellent snack.

Each of the five persimmon trees on campus have produced bountiful fruit this season! In an effort to share the persimmon love, we’re sending at least one persimmon home with every single student within our GMS community. Enjoy!

Additional Resources

- NPR: Ancient Japanese Food Craft Brings Persimmons To American Palates

- Martha Stewart: 12 Persimmon Recipes Everyone Should Make This Fall

- Wikipedia: Persimmon

About the Author

Chelsi Crawford is Greensboro Montessori School's lead environmental educator. Prior to joining our School in 2018, Chelsi was the assistant farm manager for Clemson University's sustainable agriculture program. In this role, Chelsi assisted with all farm duties pertaining to planning, food production, and harvest, in addition to managing a community supported agriculture (CSA) farm share program providing fresh produce for over 100 families weekly. Chelsi received both her Bachelor of Arts in anthropology (with a minor in biology) and her Master of Science in natural resources from North Carolina State University. She also has a published journal article focused on educational resources and dissemination of information to organic farmers throughout North Carolina.

Greensboro Montessori School partners with the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) to use Measure of Academic Progress (MAP) Growth assessments. MAP Growth is a computer-adaptive test for measuring individual student achievement and growth in math, reading, and language usage.

We've chosen MAP Growth because it is a student-centric approach to standardized testing. Unlike paper and pencil tests, where all students are asked the same questions and spend a fixed amount of time taking the test, MAP Growth is an adaptive test. That means every student gets a unique set of test questions based on responses to previous questions. At the end of each test, teachers are able to determine what individual students know and are ready to learn next.

Unlike traditional standardized tests, MAP Growth testing is administered twice a year, enabling us to measure our students' individual growth over time. Teachers may also use test results to further inform instruction, personalize learning, and monitor student growth.

While we are not a test-driven school, we know test taking is a practical life skill students need in preparation for high school and college. MAP Growth tests are one form of assessment we use, in conjunction with other methodologies of formative and summative assessment given throughout the school year.

About MAP Growth

No. As a computer-adaptive assessment, MAP Growth will provide questions to test the upper limits of your child's skills. Every student will miss questions. The MAP Growth guides suggest that students should expect to miss 40-60% of their questions.

There is no particular score for which students should aim. Instead, your child's individual MAP Growth Report will contain a RIT score. This score represents their achievement level at the time they took the test. As a partner in your child's education, we are less concerned one-time scores and will focus more attention on students' growth measures between assessments.

During MAP Growth

After MAP Growth

Preparing for MAP Growth Assessments

There is nothing families need "to do" in preparation for a MAP Growth test. We encourage families to follow the child – provide the level of support they need to feel successful. This could vary between treating an assessment day like any normal school day to practicing questions on a sample to get comfortable with the format, to talking with your child about the practical life skill of testing (i.e., tests are part of education and you should do your best, and you should not worry or stress over tests).

If you'd like to provide a strong framework for your child before and during a test, we have these tips:

The Night Before

- Relax and have fun.

- Enjoy a healthy snack an hour before bedtime.

- Get a good night's sleep.

The Morning of the Test

- Fill up on healthy, complex carbs and protein.

- Slow-release carbohydrates, like whole rolled porridge oats, whole grain bread, low-sugar muesli, and fresh fruit with a low glycemic index, help provide consistent energy levels throughout the morning.

- Proteins, such as milk, yogurt, or eggs, keep students feeling full and can lead to greater mental alertness.

- Prepare and bring a healthy midmorning snack to school.

- Arrive at school on time – no later than 8:15 a.m.

- Connect with a friend or teacher if you have pretest jitters.

During the Test

- Take three deep breaths.

- If you don't know the answer, give your best guess and move on.

Maria Montessori believed that “establishing lasting peace is the work of education...”

While many of us are focused on the end of a school year, on how the pandemic will affect our family and our jobs, and on working to support the emotional needs of our children, as we should be, I felt it appropriate to also take a moment to remind ourselves of what Maria Montessori writes about peace education. For our attention should also be focused on what is happening all around the country and world this week in response to the events in Minnesota.

Greensboro Montessori School welcomes and embraces diversity by providing a safe and supportive environment that is open and inclusive. Our community is enhanced by people from many different cultures, races, nationalities, faiths, learning and physical abilities, political backgrounds, sexual orientations and identities, ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and family constellations.

We work together to empower all of our families to share and grow in their confidence and ability to raise responsible young citizens. And, the recent tragic events in Minnesota with the death of George Floyd must serve as a reminder that we still have much work to do. Being non-racist is not the same thing as being anti-racist. As peace educators, we have a responsibility to make sure we are doing our part to foster empathy and kindness in all of our students.

Our school has always proudly had the following policies for admissions and hiring, respectively,

- Greensboro Montessori School admits students of any race, color, national and ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national and ethnic origin in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs.

- Greensboro Montessori School does not unlawfully discriminate on the basis of race, gender, disability, age, national origin, marital status, religion, sexual orientation, or veteran status with respect to recruitment, hiring, compensation, terms, conditions or privileges of employment.

We are proud that we do not discriminate. We are proud that we actively teach our students to be just and inclusive. These are at the heart of the foundations of Maria Montessori’s peace education. And sometimes this is not enough. Sometimes we must move beyond awareness of discrimination, acts of aggression, and bigotry wherever they are and at whomever they are aimed. We must also engage. How we each choose to engage these challenging times and challenging events will vary from home to home, and we all stand together with our shared value and commitment to peace education.

We hope that everyone can engage injustice when we see it, actively see our privilege where it lies, and promote equity and peace with not only our mind, but also our resources and actions. And especially to all our African American students, staff, and community members: you matter. Black Lives Matter. We see you, and we support you.

The president of the board of our accrediting body, the American Montessori Society, recently shared part of this reflection to our 16,000 members:

AMS recognizes that institutional change is required to make an impact in the larger Montessori community. Ensuring environments where everyone feels welcomed, valued, and respected is our most important charge as a membership organization. Serving as the largest Montessori membership organization does not exclude us from the institutional racism that is pervasive in associations, schools, and training programs throughout the United States. We hope that you continue to engage with us as our organization strives to be anti-racist. – Amira Mogaji, President, AMS Board of Directors

We hope that everyone can join us as we work to intentionally move from awareness to engagement.

In peace, and on behalf of the Greensboro Montessori School Team,

Dr. Kevin Navarro

Head of School

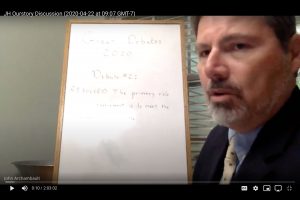

As they do every spring, Greensboro Montessori School's Junior High students recently engaged in their final Great Debate of the year in history. Students addressed and argued both sides of two debates. The first questioned whether the purposes of government are best served by an authoritarian approach. The second questioned whether the primary role of a government should be to meet the needs of its people. The debates provide Junior High students the opportunity to argue in a logical and clearly defined manner.

While The Great Debates are usually hosted in the classroom, this year's final debates were argued virtually through Google Hangouts. 57 participants, including students from both Junior High and Upper Elementary, attended the event, deepening their understanding of many forms of government and economic systems, including authoritarian, capitalist, communist, and socialist.

While The Great Debates are usually hosted in the classroom, this year's final debates were argued virtually through Google Hangouts. 57 participants, including students from both Junior High and Upper Elementary, attended the event, deepening their understanding of many forms of government and economic systems, including authoritarian, capitalist, communist, and socialist.

How the Debates Work

Teams of two or three students are given their topic in advance, but they do not learn which side they are on, for or against, until the morning of the debate. As a result, they must analyze and evaluate both sides and research and compile points and examples supporting both arguments. Each student writes two formal position papers, one for each side of the argument. This helps them broaden their thinking and mental flexibility.

The debates follow a modified version of standard debate procedure, with an opening argument, sometimes shared by two teammates; time for preparation of rebuttal; and then closing arguments and rebuttal, by the remaining member of the team. Faculty members observe, discuss and provide extensive oral feedback to the teams about the debate.

The debates follow a modified version of standard debate procedure, with an opening argument, sometimes shared by two teammates; time for preparation of rebuttal; and then closing arguments and rebuttal, by the remaining member of the team. Faculty members observe, discuss and provide extensive oral feedback to the teams about the debate.

How Topics are Selected

The topics of the debates are drawn from subject matter the students have discussed in history classes during the preceding several weeks. Students are encouraged to go beyond the class discussions in gathering information and building their arguments.

The process allows students to go beyond what they have learned and apply it to larger questions, to develop their reasoning and ability to build and support logical arguments, and to gain confidence and develop greater precision in presenting their thoughts persuasively.

How We Learn

As Junior High students move into and through adolescence, it’s imperative they receive authentic support for their burgeoning philosophical questioning, curiosity in the world around them, and deep desire for belonging within their peer group. Greensboro Montessori School honors these needs through the concept of valorization, which is a pillar of our Junior High curriculum.

Valorization is the process of understanding you are a strong and worthy person. It is the process of self-actualization and fulfillment. It is not about surviving hours of arbitrary homework or memorizing facts for the next test. It’s about completing meaningful work, unleashing academic excellence, and solving real-world problems.

The Great Debates are just one example of how Greensboro Montessori School students experience valorization by developing self-worth, skills, and courage through purpose-filled work. Learn more about how we build valorization through our science curriculum in our recent blog about Trout in the (Indoor, Outdoor, and Virtual) Classroom.

If you are interested in learning more about Greensboro Montessori School's student-centered Upper School serving motivated learners in fourth to ninth grades, we encourage you to schedule a virtual information session. We welcome an opportunity to meet you, learn more about your family, and explore Greensboro Montessori School could partner with your family.

Greensboro Montessori School's Junior High students just culminated one of their project based learning assignments – hatching, growing, and releasing brown trout.

Junior High science teacher, Tim Goetz, released the trout in a cold water tributary of the Smith River near Bassett, Virginia. It was a Friday morning in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Normally, our Junior High students would have been stream-side with Tim, and it would have been their job — not their teacher's — to complete the final step of their semester-long project. Instead, students joined Tim virtually to watch the trout meet their natural habitat.

As the trout grow, they will make their way up river into the Smith River. Along the way, they will eat land and water insects, zooplankton, worms and other aquatic creatures. They will also search for hiding places from predators, including birds and other fish. Tim Key, a member of the Nat Green Fly Fishers Club, who was present at the release said "these are some of the best fish I have every seen."

The fish were hatched at Greensboro Montessori School as a part of the nationwide Trout in the Classroom program, with support from the Dan River Basin Association, and Tim Key of the Nat Greene Fly Fishers Club. Over 250 eggs were given to the School on December 5, 2019 and the first hatch was December 10.

The fish were hatched at Greensboro Montessori School as a part of the nationwide Trout in the Classroom program, with support from the Dan River Basin Association, and Tim Key of the Nat Greene Fly Fishers Club. Over 250 eggs were given to the School on December 5, 2019 and the first hatch was December 10.

The fish were raised in a 45-gallon, cold-water aquarium at 50 degrees Fahrenheit in Greensboro Montessori's Upper School. To quickly prepare the correct growing environment, students mixed five gallons of water from the School's pond with 40 gallons of tap water. Students tended to the fish daily, including feeding, changing water, and water testing. Daily water tests included pH, ammonia, and nitrites with the goal of recreating a natural, cold-water trout habitat. This attention to detail resulted in the science room smelling more like an outdoor classroom next to a river than a traditional classroom.

Eighth grade student, Nina, was the head aquarium tender and her classmate, Ava, provided the backdrop art for the aquarium.

Prior to COVID-19, Junior High students were scheduled to travel to Virginia to release the trout themselves. Their expedition would have been part of their April Land Week, one of several weeks a year when they learn at Greensboro Montessori School's 37-acre satellite campus in Oak Ridge, N.C. With schools throughout the state suspending in-person learning, the students' land week and field trip was cancelled, but not their learning. Students participated in the trout release through a Live Lesson via Google Hangouts. Tim also documented the release on GoPro cameras so he could share the experience with the entire school community, Toddler through Junior High. After all, Greensboro Montessori School students learn everywhere, whether its the indoor, outdoor, or virtual classroom.

Prior to COVID-19, Junior High students were scheduled to travel to Virginia to release the trout themselves. Their expedition would have been part of their April Land Week, one of several weeks a year when they learn at Greensboro Montessori School's 37-acre satellite campus in Oak Ridge, N.C. With schools throughout the state suspending in-person learning, the students' land week and field trip was cancelled, but not their learning. Students participated in the trout release through a Live Lesson via Google Hangouts. Tim also documented the release on GoPro cameras so he could share the experience with the entire school community, Toddler through Junior High. After all, Greensboro Montessori School students learn everywhere, whether its the indoor, outdoor, or virtual classroom.

Learning through purpose-filled, project-based learning — like hatching, raising, and releasing brown trout into their natural habitat — is not the exception to the rule at Greensboro Montessori School. It is the rule. Our students learn through completing meaningful work, which often results in real-world benefits to the community. Through the multistep process of researching, designing, implementing, refining, analyzing, and presenting their projects, our students gain real-world skills such as resiliency, creativity, curiosity, time management, and public speaking. They also develop a sense of self-worth by understanding the value of their contributions to society and experiencing personal fulfillment.

Click here to read about about another real-world project our Junior High students are leading: inoculating, growing, harvesting, and selling shiitake mushrooms.

In addition to Trout in the Classroom, Dan River Basin Association, and Nat Greene Fly Fishers Club, Greensboro Montessori School would like to thank Oliver Rouch from K2 Productions for lending us GoPro cameras and editing our release footage. We also want to thank Tim Key for his work behind the camera.

After a long day away from our children, we parents are eager to hear all the details about how they have spent their time. However, so often our queries of “What did you do today?” are met with the same predictable response: “Nothing.” For children, distilling the many details and experiences of a full day at school into an anecdote or two is a tall order. What tools can we use to get them talking about their learning?

Vidigami

Through the Vidigami private photo sharing platform, you get to see moments of your child’s day at school. Viewing photos of your child engaged with Montessori materials can inspire great conversations. Children, especially those younger than five, are not yet able to summarize and describe the many things they experience over the course of a full and stimulating school day. However, photos offer visual cues that trigger a child’s memories and invite them to comment on specific materials and activities. There are many different ways to talk about these photos with your child, and we've provided some suggestions, which focus on your child's intrinsic motivation. Enjoy these special conversations as you allow them to teach you what they are learning at school.

- Ask your child to tell you about the photo. You may learn what they see in the classroom, or what they remember about the moment, and it may be much more than meets the eye.

- Say what you see without judgement. “I notice you are in the classroom.” “Do you know the name of that work?” “There are a lot of colors in your drawing.”

- Speak about their efforts instead of praising their product. “You really look like you are concentrating.” “Is that the first time you have done that work?” “I see your smile. What did you like about that work?” “Are you building with those blocks?”

Intrinsic Motivation

Listening to your child talk about the photos and speaking without judgement encourages your child's intrinsic motivation – it allows them to continue to work for their own sake, rather than for any praise from adults. As Montessori teachers, we get to witness this intrinsic motivation every day. It looks different at each age grouping and is a critical element to Montessori education. Many elements of the method foster intrinsic motivation without reward and judgement, such as control of error in the materials, allowing for repetition, assessment through observation, and relying on peers as sources of feedback and inspiration. Teachers try never to interrupt a concentrating child or judge their work. Instead, they seek opportunities for meaningful conversations before or after a student's work cycle.

As Montessori observed children, she saw time and time again the intrinsic motivation in the child to work through repetition for long, uninterrupted periods of time. In a book that examines Montessori’s relevance to today’s educational practices, "The Science Behind the Genius," Angeline Lillard refers to several current research studies confirming that rewards and punishments not only negatively impact intrinsic motivation, but also how a student performs on the task. Traditional reward methods used in most schools may actually hinder a child’s performance. Given the opportunity, children are capable of learning to take personal responsibility for their actions.

“Like others I had believed that it was necessary to encourage a child by means of some exterior reward that would flatter his baser sentiments … in order to foster in him a spirit of work and of peace. And I was astonished when I learned that a child who is permitted to educate himself really gives up these lower instincts.” – Dr. Maria Montessori

As a Montessori school, we believe deeply in educating the whole child: their academic, psychological, critical-thinking, moral, and social-emotional selves. In addition to the academic lessons and works your children are engaged in daily, our teachers and staff are also guiding your child through other very important lessons to help them with their moral and social-emotional development. For example, teachers give explicit lessons related to grace and courtesy, facilitate discussions at the peace table, and encourage collaborative work and play daily.

And, it turns out, research from our School confirms that we are doing this pretty well …

The Gratitude Project

We recently worked with Professor Jonathan Tudge and his team from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro ("UNCG") to study the development of gratitude as a virtue. As a virtue, gratitude goes beyond a positive feeling when something good happens. Virtuous gratitude is a disposition to act gratefully when someone else does something nice for you. Dr. Tudge explained it to me this way: “Saying 'thank you' is polite, but hardly a virtue. What makes gratitude a virtue is when beneficiaries of good deeds or significant help want to do something back for their benefactor if they have the chance to do so. That first act of generosity, followed by grateful reciprocity, leads to building or strengthening connections among people.”

In previous cross-cultural research, Dr. Tudge and his team found that most children develop this type of gratitude between the ages of 9 and 13, although the age differed depending on the cultural context. In their study, children in the United States developed virtuous gratitude at later ages than other cultures. Keeping this in mind, Dr. Tudge decided to target a new intervention designed to encourage the development of gratitude within adolescents.

Dr. Tudge and his team came to our School to explore this intervention. After working with our Upper School students, they stumbled upon a ‘good’ problem with their research: far more Greensboro Montessori School students exhibited virtuous gratitude than they expected. Our Upper Elementary and Junior High students expressed gratitude at much higher rates (67%) than did children in non-Montessori settings in the United States (46%). In addition, our students were almost twice as likely to express autonomous moral obligation (79%) than were children in non-Montessori schools (44%). Defined originally by Jean Piaget, autonomous moral obligation is a decision-making framework whereby moral decisions are made based on intrinsic motivations to do the right thing.

Dr. Tudge and his team were puzzled by these anomalous findings. Why did our students score higher than other American children, even when compared to other well-regarded private schools in the Greensboro area? And how are these findings related to Montessori pedagogy and culture?

Gratitude in the Montessori Classroom

In our discussions with Dr. Tudge, we discussed the way Montessori teachers prepare the environment to communicate honor, respect, and gratitude to the child. We also described the ways in which our teachers model gratitude and respect when they speak and interact with their students. In time, this becomes our students' definition of "how it's supposed to be.” In addition, we delineated how our grace and courtesy curriculum creates both a framework for community interactions and a schoolwide culture of character.

In collaboration with Dr. Tudge and his team, I presented the results from our Upper School students’ involvement with Dr. Tudge's gratitude study at the Association for Moral Education’s annual conference in Seattle, Washington.

In the presentation, we hypothesized that our students' high rates of gratitude could be due to several specific tenets of Montessori philosophy:

- Specific lessons about grace and courtesy provide explicit guidance on character development from a young age.

- Daily practice of grace and courtesy increase opportunities for proximal processes related to virtue development.

- Mixed age groupings of children may expose younger children to older children are further along in virtue development.

- Peer interactions encouraged from toddlerhood may increase opportunities for the development of mutual respect.

Dr. Tudge and his team also did some work with our Lower Elementary students. Tudge’s team again noted that so many of even these younger children (aged 6 to 9) expressed virtuous gratitude. Dr. Tudge reflected: “We think that this must say something about the character-based focus of the general Montessori curriculum, because a far greater proportion of Greensboro Montessori School children expressed gratitude than elsewhere.”

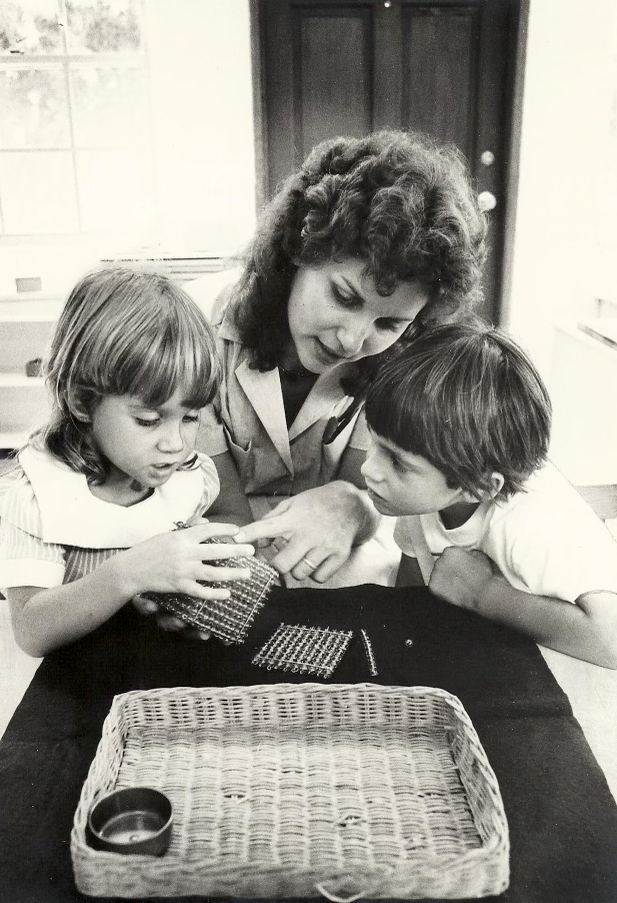

Dr. Jonathan Tudge and his team from UNCG discuss gratitude with Lower Elementary students from Greensboro Montessori School Students.

Character Education at Greensboro Montessori School

Overall, the results suggest that a Montessori environment is conducive to developing virtuous gratitude and autonomous moral obligation. These results – while surprising and interesting to the UNCG team and other researchers and educators at the Association for Moral Education conference – are not really that surprising to us. Focusing on strong character education is a key tenet of Greensboro Montessori School. A deep respect towards classmates and other people is so integral to our culture that it's not that surprising our Elementary and Junior High students authentically take their sense of gratitude to a level beyond just saying “thank you.”